Nora and TLM-P's children

Much to Nora's dismay, she and TLM-P she had 8 children. Unlike Matilda, Nora gave birth in urban settings with help at hand. She also remained healthy, so her babies were not so vulnerable: only one (Emmeline) died in infancy. Her children's choices when they grew up were firmly against marriage. Only 2 of her 4 surviving daughters married; only 1 of her 3 sons did so. While there was a dip in marriage rates at the time, and heterosexuality cannot be assumed, it is hard to escape the conclusion that one factor was their first-hand experience of the economic and personal costs of their father's fecundity.

1. Matilda (Meta) Aimee (25 September 18731)- 18 August 1939). Meta was born at 'Montpellier', Kangaroo Point, Brisbane, and was baptised at the Kangaroo Point Church of England.2) It was a difficult pregnancy as Nora had been sick for much of it.3) For at least four months during her early pregnancy, she was 'plagued' by 'a certain unpleasant lethargy of mind and body … combined with a heavy inclination to headache … [a] chronic sick headache'.4). Nora wrote to her step-daughter shortly after Meta's birth that Dr William Hobbs, a prominent Brisbane doctor, had cured her headaches so that she felt 'young and skittish again'.5) Dr Hobbs went on to deliver six of Nora's children6) and she was dismayed when she thought he might not be in Brisbane to deliver her second youngest son Robert.

In one of life's coincidences (and indicative of the small population of Queensland then), baby Meta grew up to marry, on 15 April 1896 at All Saints Church of England in Brisbane, Dr Hobbs' son Arthur, a solicitor who lived in Townsville.7) Not surprisingly, he became his widowed mother-in-law's solicitor.8) Arthur's mother was Anna nee Barton,9) no relation to Nora but a sister of (later Sir) Edmund Barton, who became Australia's first Prime Minister. It says much about Nora that, when Meta married, she and Meta's eldest step-brother shared the duties that would have been TLM-P's if he had been alive. Thomas de M. M-P escorted Meta up the aisle, but it was Nora who gave her daughter away.10) Later in life, by 1913, Meta lived in the Brisbane suburb of Ascot.11)

When Nora wrote to Rosa Praed, she often described her children. In 1883, when Meta was a young girl, Nora described her having 'little bent towards book learning preferring outdoor pursuits of any description, but she has observation & is shrewd, going straight to the root of any question & taking a common sense, & not a conventional, view of matters… She is quite on the ground, never soars to the stars but sees what is on the ground plainly & shrewdly.'; 'Meta is Papa all over from top to toe – in deposition I mean, so trustworthy & strong & self-confident I already lean on her a great deal.' However, she suffered in comparison to her more attractive younger sister Dorothy.12) TLM-P approvingly repeated to a Salvation Army officer a question Meta had asked 'Why God let the Devil make her bad?' . Her father's response, at least in 1882, was to let faith develop of its own way.(Diary, 14 June 1882)

Meta and Arthur Hobbs had two children - more information is available for family members.

Meta and her son 'Bartie' from TLM-P's photo album.13)

Meta and her son 'Bartie' from TLM-P's photo album.13)

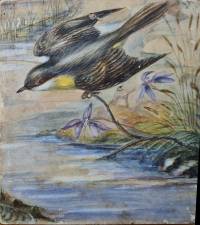

Meta, like all of TLM-P's daughters, received her basic education at home from governesses, her mother and older siblings. Like her paternal uncle William M-P and maternal aunt Emily Susan Paterson, Meta was a talented artist, judging from a lovely watercolour of a swallow and orchids by a river in the NLA.

14)

14)

TLM-P encouraged her, in 5 October 1888 while in Australia with Meta in Europe, he tried to preserve a frilled-neck lizard, presumably for Meta to draw: 'bought some arsenical soap [for 2/-] and was most of the day trying to set up the Frilled lizard for Meta, very difficult. I managed the stuffing but could not do the frills.' (6 Oct) 'Finished Meta's frilled lizard'.

She also wrote poetry.15) A 17 page handwritten story of hers survives: the copy is dated July 192516), inscribed 'For Mother', with the title “With the Sultan through Spicer's Gap. A Round Trip from Brisbane to Warwick and Back'. It is a well-written story of a family car trip with “the Sultan”, her husband, and daughter (“Miss N.S.W.”).17)

For photos of Meta as a child, click on Meta photos

2. Emmeline Mary (18 May 187518)- 5 February 187619)20) Nora hired a Brisbane midwife, Mrs Nevison, who agreed to come to Maroon for her birth and that of a neighbour. Mrs Nevison was, Nora wrote to Rosa, 'a charming old lady'21) Although Nora appreciated Maroon with its 'bright pure air', after the birth she complained that, as none of her four women servants were mothers, there was no-one on hand to advise her about baby care.22) Unfortunately, Mrs Nevison had had to leave after two weeks, as the neighbour gave birth early. Then Emmeline fell ill and Nora floundered until a neighbour advised her. Although Nora had trained as a nurse, it was at Sydney Infirmary (later Hospital) which did not offer midwifery nor (to use a modern term) paediatrics. Given this experience, none of her other babies were born at home.

There are numerous copies of this photo of Emmeline in her parents' albums. It was taken in Brisbane before Nora took her baby to Sydney to see her family. Before the photos could be distributed by her proud parents, Emmeline died. She was just over 8 months old.23) Two days after she died, Emmeline was buried in the churchyard of St Anne's Church of England at Ryde, where her parents had married.24)

There are numerous copies of this photo of Emmeline in her parents' albums. It was taken in Brisbane before Nora took her baby to Sydney to see her family. Before the photos could be distributed by her proud parents, Emmeline died. She was just over 8 months old.23) Two days after she died, Emmeline was buried in the churchyard of St Anne's Church of England at Ryde, where her parents had married.24)

Emmeline's death certificate reveals how quickly babies could die from bacterial infections in those pre-antibiotic days. Nora was staying at Richmond Terrace next to the Domain and near Sydney Hospital and her former nursing Matron Lucy Osburn, but it was to no avail when, on 2 February, Emmeline became sick with diarrhoea.25) Four days later, despite a doctor's attendance, she was dead. Summer diarrhoea was a prime cause of death for babies at the time, usually caused by contaminated milk or water. Emmeline's death certificate was sent to her father at Maroon - his fifth child to die as a baby.

While Nora was struggling before and just after Emmeline's birth - but before the baby died - Nora wrote to Rosa Praed as a kindred spirit: 'As for me I shall be bitterly disappointed if I ever see signs of another [pregnancy]'.26)

3. Dorothea (Dorothy) Katherine, B.A (University of Sydney) (13 December 187627)- 2 January 194028)) She was born and baptised at Kangaroo Point, Brisbane 29) and called Dolly when young.30) Nora was always clear-eyed about her children, but with Dorothy she had nothing but praise. When Dorothy was around 8 years old and travelling in Europe with her family, Nora wrote to Rosa that 'Dorothy is made much of by everyone, little or big. She was a pretty face, is clever & bright, & has pleasant gentle manners.'31)

In 1900 Dorothy enrolled at the University of Sydney to complete the first year of her Bachelor of Arts degree. Like her step-cousin Mabel the year before, she lived at the Women's College. Dorothy's first year was particularly successful: she passed French with first class honours and German with second class honours. She also won three prizes awarded to Women's College students: the Kambala Prize - books to the value of £5 awarded to best student who 'found it difficult otherwise to afford the necessary expenses of residence at the College'; the Grace Frazer scholarship awarded to the best matriculant entering the College that year; and she shared the French Prize, books presented to the student showing the greatest knowledge of French.32)

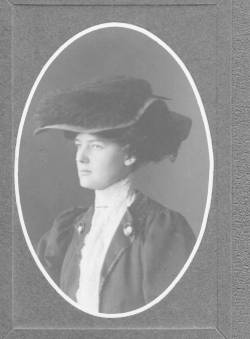

Photo of Dorothy.33)  For more photos of Dorothy, click on Dorothy photos

For more photos of Dorothy, click on Dorothy photos

Dorothy was very attractive, a quality which her mother acknowledged when she chose a verse from Tennyson to describe her: 'To doubt her fairness were to want an eye/ To doubt her pureness were to want a heart.'34) Dorothy's interests were intellectual and literary: again a book provides some evidence, one with the inscription, '1st Prize. For massive brain! Dorothy Prior. Stephanie Woodward 9.12.08'.35)

Like her youngest sister Ruth, Dorothy remained single, looking after their mother in her old age in London. Remaining single was not an odd choice for women in Australia or Britain at the time. For women born in Australia during 1871-76, just before Dorothy's birth, 17 per cent never married.36)

Dorothy was very reluctant to go overseas and one wonders what she was sacrificing to follow her mother and younger sister.37) During the war Dorothy joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) working as a cook in the buffet at Waterloo station.38) She, along with her sister Ruth, also had the task of supporting relatives who had enlisted in the war. A cousin, Max Barton, was first listed missing and, as with so many others in the chaos of war, his mother in Australia was left not knowing if he was killed, a prisoner, or wounded and unable to identify himself. Dorothy and Ruth both worked to discover the truth and wrote consoling letters to their aunt. Sadly both Max and his brother Tony died.39)

On their mother's death in 1931, the sisters permanently returned to Australia.40) They subsequently lived at 'Drak', 17 Madeline Street, Hunter's Hill. When Dorothy died, her sole executor was her sister Ruth. Her estate was valued at £5,539/10/241).

4. Alienora (known as Eileen) May (31 May 187842)- 1955). She was born and baptised at Kangaroo Point, Brisbane.43) Her engagement when she was 20 caused Florence M-P concern, writing from Maroon that Eileen was too young 'to realize what a fearful struggle life is without means', and the difficulty of raising children without the 'barest necessities of life'.44) Perhaps for these economic reasons, she did not marry Rowan Purdon Hickson (1873-1952) until December 1902. They married at Ryde, probably at St Anne's.45)

Eileen and Rowan Hickson had five children - more information is available for family members.

Gabrielle Shannon recalls that, as a child, she used to visit Eileen in her old age as 'they lived just along the street from us [in Hunters Hill]. She lived in the past and her flat was a fascinating place for a child to visit. She used to produce a play each year and always gave me a good part for which I was very grateful, but one year she put on a play she had written herself and it was embarrassing because it was so awful.'46)

Eleven months after Eileen's birth, Nora had a miscarriage. She referred to it as a 'catastrophe', but it is likely she was also relieved. As she wrote to Rosa in the same month, 'How much more pleasant it is to hear … 'How is your book' than 'how is your baby?' Alas! my mission seems to be to produce only the more commonplace article and I had such good reasons to for thinking my tasks and troubles over in that line'.47)

From January, Nora apparently lodged at Mr Jephson's boarding house 'Longreach' in Brisbane while waiting for Fred's birth.48)

5. Frederic (Fred) Maurice (949) March 188050) - 29 September 1956). He was born in Brisbane, and baptised at Kangaroo Point church.51) Despite her dismay at having more children, and concern that 'colonial boys are often great louts - and it is so difficult to know what to do with them',52) Nora was a loving mother. She told Rosa that baby Fred 'is a fine bonny fellow, sturdy enough and sufficiently like [his] Papa to console me for his existence.'53) Frederic's first names were a tribute to the Rev. Frederick Maurice, Nora's uncle by marriage and a founder of the Christian Socialist movement. For more click on Rev. Maurice and family.

A photo of Fred as a young boy:  This copy is in the ML (PXE1320) and is unfortunately behind plastic so it is difficult to photograph. Another copy of this photo is in the Oxley Library, Brisbane.

This copy is in the ML (PXE1320) and is unfortunately behind plastic so it is difficult to photograph. Another copy of this photo is in the Oxley Library, Brisbane.

Fred and his younger brother Robert first went to Bowen House Preparatory School at Ipswich; it took in boys from 7 years of age.54) This was closer to Maroon - a decision in stark contrast to what was believed the disaster of sending Matilda's young sons to school in Hobart. When Fred and his brothers were older they transferred to the more prestigious - and further away - Brisbane Grammar.55) In 1894 at Brisbane Grammar, Fred was awarded Heroes and Kings. Stories from the Greek (1890), as a prize for maths. Like most book prizes from that and subsequent decades, it appears little read.

The last Australian reference found for Fred is in 1905, when the Supreme Court was asked to interpret his father's will.56) The next reference found is to his death in New Zealand in 1956, complicated by his surname being mispelt as Murray Pryor. His death certificate reveals his sad story. He died in Auckland Mental Hospital of bronchopneumonia, but was noted as having suffered for 'years' from two other diseases, both of them highly stigmatised at the time: tuberculosis and schizophrenia. As was so often the case for mental health patients, little was known about him by the time he died. The length of time he had lived in New Zealand, as well as whether he had ever married, were consequently both recorded as unknown.57) His death was deemed natural so no inquest was performed.58)

After adding 5 children to the already large family in 5½ years, Nora understandably did not want any more. When her niece Minnie Lightoller asked her for patterns to make baby clothes, Nora wrote to Rosa Praed making that very clear: 'I sincerely hope that the mission of my layettes in future may be to serve as patterns for other people's babies' and not her own. She added, 'What a blessing that good fairy would receive from me who would give me a charm to work that end'.59) Effective birth control remained elusive, and 7 months after her letter, she again conceived.

Faced with having a sixth child, and her seventh pregnancy, and with no kindred spirit to share her concerns, she poured out her heart to her friend and step-daughter Rosa. When she was a couple of months pregnant, she commented on how another pregnant woman looked 'wretchedly ill and miserable'. Referring to pregnancy as a 'matrimonial trouble', she again dreamed of a freer future: 'Oh these babies - these babies - I am sure that a day will come (that I shall never see) when a plan of “artificial maternity” shall be matured and the present clumsy way of populating the world be done away with'. Queensland's February heat increased her discomfort, leading her to write to Rosa that 'A wife in Australia has a hard time of it … I am not [sure] that in hot climates polygamy would not be advisable.'60)

In April, she again referred to her pregnancy in negative terms, enhanced by fear that Dr Hobbs would be overseas during the delivery (she was relieved to find out he would be available) and a well-grounded fear that any replacement doctor who would deliver the baby could be drunk.61) In very late pregnancy, her discomfort led her to be more negative. Two weeks before her next baby was born she was writing to Rosa: 'Oh! these dreadful, dreadful babies'.62)

6. Robert Sterling (29 August 188163)-31 May 1962).64) When young, his family called him Robin; in later life friends called him Bob. He was named Sterling after his mother's cousins: for more, click on Sterling. Robert's birth registration gives his birthplace as Stanley Street, South Brisbane; this was an establishment, run by a Mrs Scott.65)

The move to hospital rather than home births could mean a significant rise in maternal mortality due to cross-infections, but that depended on the numbers of women cared for at once - an establishment like Mrs Scott's may well have only taken in a few women at a time. A key motivator of Nora and her contemporaries to move away from home births was access to effective pain relief.66) For Robert's birth, Nora wrote to her step-daughter, 'As the doctor was away … I did not have access to my beloved chloroform'.67) Nora was lucky as it was a face presentation and it needed a skilled midwife to deliver the baby safely.68) It was consequently

a painful delivery with TLM-P commenting in his diary, 'found Nora and the little one doing well. She had a hard time of it on Monday [for the birth]'69)

Despite Dr Hobbs' absence, TLM-P paid him five guineas. Mrs Scott's was also expensive - two guineas a week for a bed and sitting room, with a nurse paid one guinea a week to care for the baby during the dangerous month after birth. After that, Nora and baby returned to Maroon along with a nursemaid who was paid 10 shillings a week.70) As Nora was only too well aware, children were expensive. Robert was baptised at the Kangaroo Point Church of England in Brisbane.71)

In 1897, Robert was at Toowoomba Grammar School.72) A book - another school prize that appears to be little read - reveals that the next year he was at Sydney Grammar, receiving a prize for maths when in 'division 6' in 1898.73)

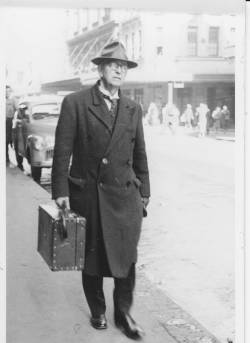

One of the ubiquitous street photos of the time: Robert M-P dressed for work as a barrister, 1955.74) For more photos of Robert and his family, click Robert M-P

One of the ubiquitous street photos of the time: Robert M-P dressed for work as a barrister, 1955.74) For more photos of Robert and his family, click Robert M-P

Robert was admitted to the NSW bar in November 1908; as a barrister, he specialised in probate law. Family lore has it that he did not enjoy that area of practice largely because it so often involved bitter family disputes. It is also understood that he challenged the power of law clerks to distribute briefs - he lost that battle and thereafter the clerks avoided giving him briefs, much to the detriment of his practice.75)

Robert M-P was a political conservative, a prominent Mason and active in his local community of Hunters Hill, becoming its mayor in 1935. During World War II he was employed as a censor.76). Murray Prior Reserve, George Street, Hunters Hill is named after him.

77)

77)

He was also active in community groups. In c.1901, he was the founding Honorary Treasurer of the Gladesville Volunteer Fire Brigade.78) A small medal dated March 1902 has inscribed on the reverse that it was presented to him 'by the G.C.& D. Society for his zealous work as Secretary' - just what was that Society is unknown though G perhaps stands for Gladesville.79) He was also a founder, President and keen actor for the Hunters Hill Playreading and Dramatic Club.80) While in his twenties, he wrote the genealogical history of his family, 'The Blood Royal of the Murray-Priors'.

Robert married on 22 April 1908, Estella (Stella) Augusta Herring 1883-17 September 1968.81) She was born at Gladesville on 4 March 188382); her brother Sydney had married Robert's step-niece, a daughter of Florence and Thomas de M.M-P. Stella Herring was reputedly brought up by nannies in an austere fashion, normally seeing her parents only to say goodnight, and at a set and limited period on the weekends.83) Her father was Gerald Herring, a Mayor of Ryde: Herring Road, North Ryde is named after him. On her marriage certificate, Stella gave his occupation as 'gentleman'; Robert described TLM-P as a grazier. After their marriage, Robert and Stella lived at 1 Yerton Avenue, Hunters Hill (the noted artist Nora Heysen lived opposite at no. 2 Yerton Ave). With the death of Robert's sister Ruth M-P, they moved to her home at 17 Madeline Street, Hunters Hill. Click here for certificates.

Robert and Stella had five children - more information is available for family members.

In his will, Robert left a collection of his step-sister Rosa Praed's books to the Royal Geographic Society of Australia, Queensland branch.84)

Nora was dismayed when she again became pregnant, around two years after Robert's birth. She apparently delayed telling Rosa until she could put it off no longer: “Open confession is good for the soul and nothing can be hidden forever, and you can perhaps imagine some little of the mortification, chagrin and disgust [with] which I have been forced to recognise myself as once again in the valley of the shadow of a baby. … All pleasant plans were broken up and at an end. So many more years of necessary repetition in this quiet dull place, of which by the bye, I am heartily fond when I do not feel eternally tied to it … [baby] being forced into world where he is not at all wanted.”85)

7. Julius (Jules) Orlebar (25 March 1884 - 6 October 193186)). Nora's 'poor little morsel' was born at 'Ervingstone',87) Stanley Street, South Brisbane88) and baptised at the Kangaroo Point Church of England.89) Julius never married and had no known children. His second name of Orlebar was the family name of TLM-P's maternal grandmother; when TLM-P visited his daughter Rosa Praed in England, they visited the widowed 'Mrs Olebar' whom he thought was 'nearly 80 a very nice looking old lady' with two daughters. The Olebars had fallen on hard times and were in the process of leaving their ancestral home.90) TLM-P also refers to seeing Miss Olebar in England and mentions the 'Olebars farm at Warrnambool Victoria'91)

Julius was three months old when Nora wrote to Rosa about her 'morbid thoughts and feelings' during pregnancy and what we would now call a mid-life crisis (Nora was then 37 years old):' You have brought a life into an uncertain world of wrecks and disease and dynamite explosions. Your heart’s love is irrevocably invested in that life.“92) As far as childhood diseases went, necessity meant that she had gained considerable confidence, writing to Rosa that 'Fortunately I am now quite as good as a Doctor with baby complaints', which was fortunate given she also assured her that 'as little as I care for having babies, I should like losing those I have still less.'93)

Like his brothers Fred and Robert, Julius initially went to school at Bowen House in Brisbane, the preparatory school for Brisbane Grammar.94) While still a schoolboy, he moved with his mother and other siblings to Sydney where they lived in a home called Karlite (or Karlyte) at Gladesville.95) In 1901, the 17-year-old won two prizes at a Flower Show to raise money for the Anglican church at Gladesville (his sisters, Eileen and Dorothy, entered the table decoration category, but were unsuccessful).96) He was listed in the Wise Directory of 1907 and 1908 as a 'farmer' living at Clifton.97) In 1909, 24 year-old Julius was described as a stockman in the Gulf of Carpentaria and 'a bit of a mug'. The latter was because, on the train down to Sydney, he was fleeced £4 at cards - understandably, he was 'greatly agitated' at the loss - in 2017 values it was around $548, a lot for a young stockman to lose before even arriving in the city.98) He gave his address in Sydney as 'Abalar', Darling Point Road, Darling Point.99)

Sometime after this widely reported incident, he went to the Kimberleys in Western Australia. It was a popular destination for Queensland graziers eager for new land, such as the famed Durack family.100) Julius's sister Ruth wrote that he had been a special constable in the north of Western Australia to deal with Aboriginal resistance which took the form of cattle spearing and murder.101) In 1911, he was part of an exploring expedition to collect zoological and botanical specimens as well as discovering land that was then unknown to the white settlers. The Expedition initially consisted of three experts: the leader was Perth Museum's zoologist, Charles Conigrave. He was accompanied by Lachlan McKinnon and Roy Collison, both 'zoologists and passionate ornithologists'. Julius and three other bushmen joined the party at Wyndham: the others were two members of the native police known as Killy and Quart-Pot and another white man, Jack Wilson. The Expedition left Wyndham in June 1911; the three leaders returning to Perth in March 1912. Their discovery of land suitable for cattle meant they were feted on their arrival back in Perth, with over 100 newspaper articles published about the expedition. Today as much interest is in their recording of Aboriginal art. The outcomes of the Expedition included giving European names to two rivers and identifying a 'new', at least to the white settlers, form of Indigenous art, that of ground figures.102) There are two photos of Julius and other members of the exploring expedition held by the National Archives of Australia. Click on Julius second from left back row and Julius far left.

Julius was still in West Australia when World War I began, changing the lives of all such young men. On 8 November 1914, he enlisted as a Private in the 10th Australian Light Horse Regiment. On enlistment he gave his occupation as a grazier and his record shows he was a tall man (6'2½”) who weighed 12 stone.103) According to his sister Ruth, the Light Horse was a logical choice as Julius was a good horseman. Julius sailed from Australia in February 1915. His regiment's first action was at Gallipoli; thereafter it remained in the Middle East. In 1915 he was promoted to corporal; his cousin Tony Barton commented that, 'I had a long yarn with Jules the other day and he seems to be much the same as he always was. He is a corporal but I should think his lack of self-confidence was a bit of a draw back to him.'104) Despite that lack of self-confidence, he was again promoted, in 1917 to Sergeant. Julius was wounded in action at Gallipoli in 1915, with shrapnel in his leg.105) Ruth reported that he had been taken to the hospital on the Greek island of Lemnos; when he returned to his unit, out of 1,000 men he could find less than 50 still alive.106) This once fit and healthy man was again sick in December 1915, and hospitalised several times in the remaining years of the war. As soldiers just appeared on casualty lists with no details, and Julius had given his mother in London as his next-of-kin, his Australian relatives were left in the dark until details went first to London then back to Sydney. Both Miss E. Hobbs (a niece?) and his brother Robert accordingly wrote directly to the army (in the latter case, the Minister for Defence) asking for quicker information. A month before the armistice, Julius was again in hospital, this time with influenza, the beginning of the world-wide pandemic which would kill more people than the War. He remained in the army for 1919, was given medical clearance in May before returning to Queensland to be demobilised. It is probably significant that Julius and the others on the ship were taken straight to a hospital.107)

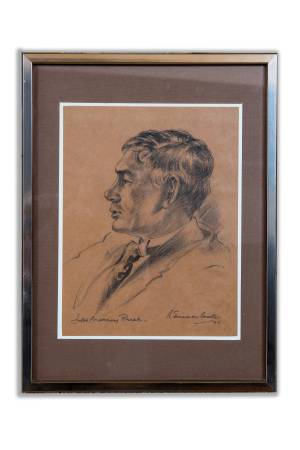

A very faded and damaged photo of Julius Murray-Prior108):  Sketch of Julius.

Sketch of Julius. 109)

109)

Little is known about Julius' life immediately after the war. By 1927 he was living at Stanthorpe, perhaps on one of the notoriously inadequate soldier settler blocks there (to check). Calling himself Jules Murray-Prior, he was also trying to find work as a stage and screen 'character' actor: click here for his ad110)

In 1931 Julius died, aged 47, after shooting himself in the head. Sadly, his end was not quick, as he died in Stanthorpe Hospital.111) He was then described as an orchardist at Broadwater, Stanthorpe.112) His Australian experiences and army service may provide one explanation for one informant's belief that he was an alcoholic and was often found drunk on his horse outside his home in the early hours of the morning.113) His domestic and overseas war experiences could also be an explanation for his sad end. So too was the fact that 1931 was near the depth of the Great Depression. As an orchardist, Julius was unlikely to have been able to make a living at this time. It may be a factor too in his not marrying, if he had ever been so inclined, as he probably could not afford to support a wife and any children.

Julius left an estate of £2,492 - around $223,449 in 2017 values.114) In a will made 4 months before he died, Julius left land, presumably his orchard, worth £696 to Miss Mary Myrtle Macdonald, then living in Brisbane. She was also his sole executor of the will.115) Mary (1889-1958) never married.116)

Nora apparently suffered 'perineal tears and subsequent haemorrhage' during Julius' birth 117) but nevertheless, eight months later she conceived again and desperately, despairingly, sought to induce an abortion. With her earlier pregnancies, she had taken care not to miscarry, cancelling travel and postponing dental work.118) This time was very different. In a much-quoted passage, she wrote to Rosa: 'What will you say to me? How will you manifest your disgust? When I tell you that I am again sick, sorry and expecting … When it first began I resolved to try heroic remedies - so … had sixteen teeth taken out - but … I was much pulled down and very sick after it, but my prospects remain the same. What will become of all my little ones of whom the world stands in no need, how will they find niches & sure foothold for themselves amongst the many struggling ones who are each pushing for themself. There is certainly not room for them all to walk safely - some of them must go to the wall. No mother even bore children into the world with more foreboding than I do…'119) Fortunately for Nora, it was to be her last baby.

8. Ruth Angela (27 July 1885-15 August 1961).120) The birth notice121) stated that, like her brother Julius, Ruth was born at Ervingstone, presumably a private maternity hospital: 'MURRAY-PRIOR.—On the 27th July, at Ervingstone, South Brisbane, the wife of Thos. L. Murray-Prior, of Maroon, of a daughter'. Dorothy, Alienora and Ruth were all baptised at the Kangaroo Point Church of England by the Rev. D. A. Court.122) As the youngest child, Ruth was seven when her 73-year-old father died. When her mother chose a verse to describe her, probably in the 1890s, it was one from the poet Lowell, 'I know not how others see her/ but to me she is wholly fair.'123) From shortly before World War I, Ruth lived in England (mostly London) with her mother and her elder sister Dorothy. After Nora died, Ruth and Dorothy returned to Australia in 1931. The sisters spent the rest of their life at 'Drak', 17 Madeline Street, Hunters Hill.

In 1903 the 18-year-old Ruth wrote to her 'Dearest Old Mother' saying that she would like to be coached in mathematics, if Nora could afford it.124) If the coaching occurred and was for matriculation, it succeeded as she enrolled in the University of Sydney and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1906. Her success meant that for three successive years she, her brother Robert (in 1905) and her sister Dorothy (1904) all graduated from that University with a BA.125) Ruth shared her mother's and her sister Dorothy's intellectual interests: in 1904 all three attended the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science congress in New Zealand.126)

Ruth was the more radical and adventurous of her sisters and, by 1910, she supported women's suffrage and free trade.127) It was Ruth who pressured her mother and sister to travel overseas, to satisfy what she called her 'awful craving for foreign travel'. As it was, Ruth wrote to Rosa Praed in 1910, during the last year they had travelled around 4,000 miles but encountered nothing new: 'always to bump up against the same prosaic, money-making Anglo-Saxon race.'128) Later, Ruth's brother Robert swore that the purpose was to increase his sisters' employment prospects: 'My said sisters are both graduates of the Sydney University and the main idea of the visit abroad was to enable them to become more proficient in the French German and Italian languages so that they would be in a more favourable position to teach on their return to New South Wales'.129)

In England during World War I, she supported the war effort. She served with the Young Men's Christian Association in 1914. From around August 1915, she joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD). 130) In around March 1917, she helped run a YWCA canteen in France.131) While her loyalty to the British Empire was unquestioned, her experiences inflamed her Australian nationalism - a dual sentiment strongly shared by her mother's family and promoted by her cousin Andrew Barton (Banjo) Paterson s well as Australian nurses working in British hospitals and clearing stations.132).133) For more on Ruth's wartime experiences, click on Ruth during WWI.

Ruth had ambitions to write and was encouraged by Rosa to put her literary talent 'to profitable account'.134). However, Ruth found Rosa's criticisms dispiriting; she wrote that she was mortified not to see the defects before and will not try again to write a book.135) Her talent is evident in a light-hearted romantic short story she wrote with Rose Jardine136) called 'The Morse Code'. It was published in June 1910 in the prominent literary magazine Lone Hand - it can be viewed at The Morse Code. She had a close friendship with New Zealand writer Edith Lyttleton, who wrote under the pen-name of G.B. Lancaster. While they had both published in the Lone Hand, their friendship began in London during 1913.137) They bonded over literature, but another common factor was that they both sacrificed a great deal of their life to look after their mother. Lyttleton's ironic comment that she and Ruth should stop being so unselfish and 'Do Something that will keep us busy with remorse for the rest of our days' was impossible for either to contemplate seriously.138)

This 1929 sketch of Ruth, like the one of her sister Dorothy, is by her cousin Isabel Huntley.139)

This 1929 sketch of Ruth, like the one of her sister Dorothy, is by her cousin Isabel Huntley.139)

In her old age, Ruth was remembered with love by children. A relative Gabrielle (Gay) Shannon recalled her as 'so sweet to children and always had time for me to show me the ducks and her cockatoo'.140) My memory of meeting her as a 9 year old was also someone who was very kind.141) Her death notice included the statement 'loving aunt of her nephews and nieces'142)

After Ruth died, 'Drak', the house she and her sister Dorothy had lived in at Hunters' Hill was bought by their brother Robert. Robert and his wife Stella lived there until they died. After Robert died, his son David joined his mother living at Drak. For a number of years, Helen Murray-Prior also lived there until her grandmother died.

Key Genealogical Sources: Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Colonial Gentry, Melbourne: E.A. Petherick, 1891-95, p.50; Owen Lloyd, Jeremy Long and Barbara Dawson, Descendants of Robert Johnston Barton & Emily Mary Darvall, 1993; Robert M-P, The Blood Royal of the Murray-Priors, pp.18-19; Thomas Bertram M-P, Some Australasian Families Descended from Royalty, ms, n.d., pp. 15-18.