'Air castles': Royalty and the Butler, Morres and Lodge families

Most families have their ‘castles in the air’, stories embellished with dreams of what might have been. This section deals with the main 'castles in the air' of past family historians. Aspects of these stories regularly pop up in online searches, and we include them here so you know why we don't think they are the most relevant aspect of our family history.

1. Royalty

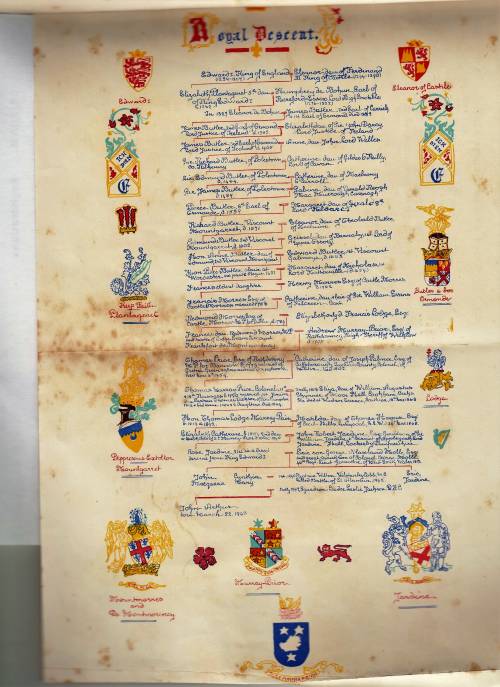

For the Murray-Priors of the late 19th and early 20th century, their chief 'castle in the air' was their royal ‘blood line’. Robert M-P, Thomas Bertram M-P and TLM-P's grandson Robert Hickson each demonstrated that the family could be traced back to various royalty including King Cerdic (d. 534), Emperor Charlemagne and King Edward I.1) It is very difficult to obtain irrefutable evidence of descent going back so many generations and at least one authority considered that Rowan Hickson's family tree was flawed as 'many of the pedigrees which he has compiled are inaccurate and follow secondary sources and 19th century errors.'2). In the past, that TLM-P was a 'direct descendant of Edward I' was considered important enough to figure in his entry in The Australian Encyclopaedia.3) Even the Royal Geographical Society of Australia joined in, with the 1953 publication in their Queensland Geographical Journal of Isobel Hannah’s ‘The Royal Descent of the First Postmaster General of Queensland’.4) The following chart from that article is titled 'Royal Descent' and highlights the Jardines as well as Murray-Priors. It is a good example how selective a line of descent could be.

With hindsight, this fad suggests antipodean ambition in a British colony where there were few members of the British aristocracy. Nineteenth century Britain was permeated by its strong class system and it is understandable that some Australian colonists saw themselves as potential candidates, should the opportunity arise, of filling the vacancy near the top of the social pile. There is a further significant factor in TLM-P and others of the family emphasising their family history: the colonies were places where many migrants reinvented themselves, shedding marriages and giving themselves a leg up the social scale.5) Other colonists like TLM-P needed to prove their family’s ‘gentry’ status to establish that his bona fides were genuine – it also helped to present them in the most advantageous light possible.

The colonial/post-colonial fad for tracing descendants back centuries to discover royal ancestors is culturally understandable, but today it doesn't pass the 'so what' test. Your number of direct ancestors double each generation – you have 2 parents, 4 grandparents, 8 great-grandparents etc. By the time you go back 10 generations, you have up to 1,000 direct ancestors (probably less as it's likely some appear more than once). That means that ‘at five generations, you are likely to have only 3.125% of each ancestor's genes, and by seven generation, you are likely to have less than one percent’. It's ‘biologically insignificant to have distant illustrious ancestors’.6) It is also arbitrary to follow one particular line of descent among so many and varied ancestors. In the case of the Murray-Prior genealogies showing royal descent, they alternate between male and female ancestors, dodging down the family tree to reach the desired outcome. In this history, we put aside genetic fantasy to explore the more direct and recent members connected with TLM-P’s family name.

2. An Aristocratic ‘Air Castle’ and the story of the lost baby: the Butlers

A select few families in Ireland wielded a huge amount of power and it is understandable that others dreamt of being part of their network. One of the most eminent families in Ireland was the Butlers. They prospered in their role as English overlords and built an impressive number of castles that are tourist attractions today.

Photo: Kilkenny Castle (one of the Butler residences).

Some past Murray-Priors saw the Butlers as an important focus when compiling family trees, especially Robert Hickson who was a member of the Butler Society and made special mention of Butler “cousins”.7) His main claim to a connection with the Irish family was through the marriage of Ethel Nora M-P (1884-1959) to Royston Butler (1874-1961), though Royston Butler's connection to the aristocratic Irish family appears to be remote. Robert Hickson, like others, found another connection to the Irish aristocratic family - one that the description 'remote' is not nearly strong enough. He and others started with England’s Edward I (reigned 1272-1307) through to his grand-daughter Eleanor (Alianore) de Bohun (c.1302-63). Note that Edward I had 17 or 18 (legitimate) children so his descendants are numerous! Alianore married James Butler, 1st Earl of Ormond, 2nd Earl of Carrick and Lord Palatine of Tipperary, Ireland. By jumping from sons and daughters as required, you can get from Eleanor/Alianore to Frances Butler, elder daughter of the Hon. Colonel Piers Butler, who married Hervey Morres: their great-granddaughter Frances Morres married Andrew Murray-Prior. Not a close connection!

A possible Butler ‘air castle’ features an illegitimate Butler baby. It was easy to believe that parentage was not always what it seemed in the past when no-one could conclusively prove their parentage; when abstinence was the only effective contraception; and when children born of parents who were not married 8) were common. Concerns about 'lost' children were part of the popular culture, tapped as a source of comic/dramatic inspiration by Gilbert & Sullivan, Oscar Wilde etc. Usually these stories coalesced around a powerful, and hitherto unacknowledged, father. One example is Sir John Conway, an equerry to (later Queen) Victoria’s father and dominating influence during Victoria's childhood. Victoria banished him from the court when she ascended the throne. One explanation for Conway's bullying of Victoria is that he believed (against all evidence) that his wife was Victoria's half-sister, an illegitimate child of her father. The eminent historian A.N. Wilson comments that it is unknown if Sir John’s wife shared – or even knew about – her husband’s belief in her royal parentage.9)

The Murray-Prior/Butler 'lost child' story, related by Robert and Thomas Bertram M-P,10) begins with the above Andrew M-P's son, Andrew Redmond Murray-Prior (1786-1860), having an affair with his distant cousin Lady Sarah Butler (c.1790-1838). This is possible: they were both in their early twenties and unmarried at the time. Robert M-P recorded11) that Lady Sarah became pregnant, but was forbidden to marry Andrew because her parents disliked him (as likely, as a younger son, he was not much of a catch for a Butler lady). When Lady Sarah's baby was born in April 1811, her parents had the baby whisked away to be raised by foster parents. Despite efforts, neither parent was ever able to discover their baby’s given name or whereabouts. Lady Sarah was ‘distraught for some years’, though in October 1812 she married another relative, the Hon. Charles Harward Butler. It is feasible that this marriage was a strategic one to contain the scandal within the family. Such an action would be especially likely as the birth would make it obvious to a bridegroom that Lady Sarah was far from being a virgin. Aristocratic women tended to be free to have affairs with suitable men, with resulting illegitimate children, but there was considerable anxiety that they first produce a legitimate ‘heir and a spare’.12) Certainly the Hon. Charles was amendable to a bargain and so eager for advancement that, to try to secure an inheritance, he later added relatives’ surnames to his, becoming the Hon. Charles Harward Butler-Clarke-Southwell-Wandesford13): yes, really!

Robert and Thomas Bertram M-P related how the baby, the granddaughter of an Earl and daughter of one of the wealthiest families in Ireland, was named Elizabeth and given the surname of Marks. She reputedly came to NSW in 1836 to work for the Innes family at Lake Macquarie. On 4 July 1836, she married a fellow employee, Alexander Cameron: this marriage in the Church of England at Port Macquarie is listed in the BDM. Robert M-P wrote that Alexander Cameron later enlisted TLM-P’s help in getting Elizabeth’s parentage recognised, but all the younger generation of Butlers did was to indicate their regret and acknowledge the birth.

Painting of the Innes estate at Lake Macquarie, 1839.

Painting of the Innes estate at Lake Macquarie, 1839.

It's an intriguing tale, yet one that raises a number of red flags.

While it was normal for Victorian-era husbands to write on behalf of wives, there is no mention of Elizabeth (like Sir John Conroy’s wife) having any knowledge of her husband’s intervention. In this case, a complication is that Elizabeth Marks was not literate, as indicated by her signing her marriage certificate with a cross.14) As well, the dates/place Robert and Thomas Bertram M-P give for Elizabeth and Alexander’s deaths are incorrect (cf. BDM). Most importantly, the Eliza Marks who arrived on the James Pattison on 11 December 1836 was then aged 20. That means her birth year was 1816 or, if she had a December birthday, 1815. In either case, she born after her supposed mother married which blows the story of the passionate young lovers who wanted to marry out of the water. Ancestory.com repeats the story, but their source appears to be Robert and Thomas Bertram M-P's tale with some added errors such as Sarah and Andrew marrying.

A tendency to fantasy could also be inferred from a descendant of Elizabeth and Alexander Cameron: Sarah Jane Coombes (nee Cameron). If one (rather dubious in that no evidence is provided) source is correct, Sarah fanatised about the Murray-Priors becoming Australian monarchs, with her family having titles - all based on the supposed Butler connection.15)

Typically of many family legends, there is another version of the story. Jemima M-P told her step-brother TLM-P that their father, when he was 17 years old and in the army, was quartered over a stable belonging to the Marquis of Ormond. As the Marquis considered Thomas a kinsman, he arranged for him to stay in the Castle with the family, which included Lady Eva Butler. It ended with Thomas being sent away and 'Lady Eva being locked up … [and she later] married, ran away from her husband, was divorced and ended her life in a show cottage W. Llangollen in Wales, living with a sister.'16) It is a fascinating mishmash as it links the family to the famous story of two women (Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby) who rejected and/or were rejected by, all male suitors and made several attempts to run away together. They eventually succeeded and lived happily sharing a four-poster bed in their cottage in Llangollen, Wales, gaining a reputation as delightful eccentrics. Alas for a good story, there is no evidence that young Thomas (or any man) ever seduced Eleanor/Eva.17)

There is yet another Butler story (though no suggestion of ex-nuptial birth) cited on Jane Austen's world from The Court Journal: Gazette of the Fashionable World, 319, Windsor, 5 June 1835, p.357: “Another Elopement–A considerable sensation has been created in Dublin by the disappearance of the lovely daughter of Sir Thomas Butler, of county Carlow, with Captain Gosset, son of the Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant. An attachment had existed between the parties for some time, but the friends of both were averse to the marriage, in consequence, it is said, of “almighty love” being their only patrimony. The lady is one of ten children.” It is possible a garbled version of this story fed into the rumours around a Butler-Murray-Prior baby.

The verdict? Most likely, Elizabeth Marks had nothing to do with the Murray-Priors or Butlers, though possibly an affair between Andrew R. M-P and Lady Sarah Butler that resulted in a baby did occur.

3. A more grounded ‘Air Castle’: the Morres and Lodge Families

Four Generations: source of names and pride

| Hervey Morres, 1625-1724 | m. | Frances Butler |

| Francis Morres (b. c.1680) | m. 1706 | Catherine Evans |

| Redmond Morres (171118)-1784) | m. 1740 | Elizabeth Lodge(1713-1806)19) |

| Frances Morres (c.1751-180620)) | m. 29 April 1772 | Andrew Murray-Prior (c.1747-95) TLM-P's great-grandfather |

The Table above summarises the connection between the Murray-Priors and the Morres/Lodge families.21) It begins with Hervey Morres marrying Frances Butler: their great-granddaughter (another Frances) married Andrew M-P, TLM-P's great-grandfather. The Morres family tended to be successful, wealthy (Francis and Redmond, the second and third generation above, both married an heiress) and were public figures. The Morres family's use as role models for children increased from 1816 when Lodge Morres (brother of Frances M-P nee Morres) was awarded the title Viscount Frankfort de Montmorency. He choose de Montmorency because of what Burke's Peerage called a 'genuine but mistaken belief' that he was descended from the distinguished French family of that name. When visiting England in 1882, TLM-P visited T.L. de Montmorency at 78 Old Bond Street, London and the next day, again saw him as well as his son.(Diary, 27-28 August 1882)).

Generations of Murray-Priors drew on Andrew M-P's august in-laws when choosing names for their children. The second name of TLM-P, Andrew M-P's great-grandson, was Lodge while his uncle was Lodge Morres M-P. Many of TLM-P's children appear to be named after this family. Catherine and Elizabeth were popular names and also the second names of TLM-P’s step-sister Louisa; Lodge and Morres could be named after his uncle; but there appears no reason other than identification with the Morres family when three of TLM-P's sons were named Hervey, Redmond and (as a second name for Thomas) de Montmorenci (a variation of Montmorency). Louisa, TLM-P's step-sister, urged that de Montmorenci be the second name for another of his sons: this suggestion was vetoed by his second wife Nora as being 'too pretentious for the colonies“.22)

TLM-P and Louisa M-P were not the only M-Ps to identify with the de Montmorencys - Swire Murray-Prior was from another branch of the family and his death notice, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 1993, p.35, gives his second name as 'de Montmorency'.23) Swire was born in 1911 to Bertram A. and Ida L. M-P.24)

Photo: Castlemorres House, Kilmaganny, Kilkenny: it was demolished in 1978.