Character, Possessions, Photos, Death

TLM-P's actions and possessions as well as his writings reveal much about his character, and this section gives additional hints about what he was like. To put his attitudes in historical context, see Hogg, Robert. 'The Most Manly Class that Exists': British Gentlemen on the Queensland Frontier. Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol. 13, 2011: 65-84. cited 02 Jun 20.

Religion

TLM-P's diaries and one of his account books1) indicates that he was an Anglican with conventional beliefs but questioning attitude. His cheque list in 1867 shows that the family gave money for 'sittings' in St John's Brisbane's pro-cathedral). In this time of intense Catholic-Protestant hostility, he was not a rigid Protestant, as shown by his £1 cheque for a ticket for the Sisters of Mercy bazaar in June 1867.2)

Character

The view of Australia's Representative Men was that TLM-P had a 'most courteous manner and kindness of feeling'. Further, 'all classes can approach him and be received without ostentation'. His private character matched his public image, with his 'family and acquaintances' holding him 'in great esteem'. He retained strong ties to his country of birth, visiting there in 1881, 1885 and 1888.3) The Brisbane newspaper, in his obituary choose to praise him by stating that 'his courtesy and urbanity won the esteem and hearty goodwill of the members of the [Legislative] Council'.4) A contemporary, Arthur McConnel, described him as 'a handsome man in appearance, sparsely built, and fairly tall, with very dark eyes. he did not give one the idea that he was once a sailor, but more like an officer of a crack cavalry regiment. His style was autocratic but could unbend.' 5). An unidentified newspaper clipping just after TLM-P died highlighted a key characteristic: 'Despite his array of names and his early-century manner, Mr. Murray Prior was one of those squatters who worked as hard [physically] as their men', a judgment supported by his diaries and his second wife's letters.6)

Like other squatters,7) he displayed considerable anxiety about re-establishing his family's gentry status. Unlike his father, TLM-P insisted on the Murray-Prior surname rather than just Prior. It was TLM-P who wrote to the College of Heralds to confirm the family's heraldic entitlement. Once it was confirmed, he had the M-P crest engraved on many of his belongings. As in the case of this watch, it also served as a useful point of identification in case of thief. 8)

8)

The M-P seal apparently acquired by TLM-P or his son, R.S. M-P.

TLM-P's son Robert, who was 10 when his father died, described TLM-P as 'justly renowned for his courtly bearing and usage of words. He was veritably an aristocratic statesmen of old and could smile through the harshest of Parliamentary insults' The only thing that cause him to lose his temper was any insult to Queen Victoria or towards 'Monarchy as a phenomenon', on the apparent grounds that the Queen was 'his distant cousin'.9) This view of TLM-P has been accepted unquestioningly by other writers, perhaps most influentially in his entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Certainly if he adopted an overly courtly bearing, it fits in with Rachel Henning's perception of him in 1863 as 'I suppose it does not require any great talent to be a Postmaster General. I hope not, for such a goose I have seldom seen. He talked incessantly and all his conversation consisted of pointless stories of which he himself was the hero.'10) Yet TLM-P's diary for 6 October 1863 suggests a more pertinent reason: he described the Henning's house as 'a comfortable humpy' and dismissed Rachel and her sister with the slighting comment that 'Mr Henning … has unmarried sisters living with him, somewhat passed their first youth'. It should be noted too, that TLM-P may not have been at his best: he stayed with the Hennings while on a tour of inspection that would leave most people exhausted: during 54 days inspecting postal services, he rode 1,017 miles (1,636 km) as well as travelling by sea. Additionally, if TLM-P was such an ardent monarchist it did not stop him marrying Nora Barton who blithely wrote to his elder daughter that of course she thought Australia should become a republic, though she did not expect it until the next generation!11)

The courtly politician was also typical of the pioneer settlers in that he prided himself on undertaking hard physical work. Isobel Hannah is likely to be correct when she stated that this 'cultured man, appreciating the finer things of life, … was withal a worker in the truest sense. Popular with his employees, sharing with them a strenuous day on the run, after sheep and cattle, I have known men, who served him when young, retain to the end of their own long lives the utmost affection for Mr. Murray-Prior.'12) Perhaps because he was used to hard physical work, he could be anxious that his status not suffer. One well-known story, with numerous variations, has someone hailing him as a fellow driver of a bullock team. TLM-P was supposed to have indignantly replied that he was not a bullocky, but 'A gentleman “squattah” driving my own team'. It was said to have become a widespread joke for bullockies in the area to be called 'gentlemen squatters driving their own teams' - one of a number of times TLM-P had to be reminded that he lived in a more egalitarian environment than the one he was brought up in - especially as the son of an army officer.13)

In contrast to the above story of his snobbishness, TLM-P's diary of his 1882 visit to England shows him as avidly curious and willing to engage in friendly talk with anyone he thought interesting. On the 26th May, he records a - for him - typical incident: 'passing a butchers shop I was having a look at their beef when … [butcher] asked me if I would like to see the shop so we got into conversation and he shewed me all over asking “my missus” [actually his step-sister Jemima] to come too … I told the man I was in the trade and had an invitation to his farm which I shall avail myself of some day … I was glad to be able to compare [his beef] .. with ours as my eye was fresh for a comparison.' Similarly when visiting Jemima at Portsmouth, he called into the local butcher's shop to get the men's opinion on Australian meat. The day before he had accidentally bought a 3rd class rather than 1st class ticket on the train from Rosa's to London, but soon 'got into chat with some decent men of the trade or manufacturing class and reaped as much information from them as I could. Found the Australian wheat liked …'.14). His 1882 diary shows considerable appreciation for the hard lot of English servants. He thought that the Misses Sterlings' servants were good because the mistresses were so nice, making it a happy home for all.15). One act of consideration was particularly appreciated: he gave his step-sister's servant 5 shillings as a present on her 18th birthday, commenting that it 'delighted the poor girl who told Jemima no one had done it before.'16)

The nature of the praise by his second wife is also worth noting. It could be expected that she would praise him when writing to her step-daughter, but their correspondence was an unusually frank exchange between friends. The qualities she singled out was his consistent hard work, 'energy and foresight'.17)

His diaries, as well as his friendship with Leichhardt, reveal his intense scientific and philosophical curiosity. When he was in London in 1882, he got chatting to a Salvation Army officer, commenting that Meta, then 9 years old, had asked, 'Why God let the Devil make her bad!' TLM-P told the officer that he thought this and other tricky questions should be honestly tackled by clergyman rather than the issue being dismissed with an exhortation to have faith.18) While he shared the common view of his time that religion was necessary, he was tolerant of sectarian differences. A High Church Anglican service amazed him with its similarities to Catholic rituals, but while he privately considered the service 'too much like acting and mummery', he conceded others may feel differently 'and if sincere may do good'.19)

It is a relief, given the number of children he had, that the evidence of his 1882 diary is that he was loving and patient with his grandchildren. He is pleased when he can be with them, and a bit of a soft touch. On 13 August 1882, for instance, he wrote in his diary that he was up late because Rosa's two young boys had come into his room before he got up and insisted on a story - this was apparently their morning routine.20) In this diary there is also a reference to taking Meta to the park and other indications he was an active, loving father.21) A letter of his to Florence M-P indicates that his troubles with his adult children clouded his attitude: 'Kiss baby for Grandfather with his best wishes - 3 years old - it is to be hoped she will remain baby - Children are not an unmixed[?] blessing'22)

TLM-P's conflict with Elise Barney of the Brisbane Post office has resulted in him being an anti-hero for numerous feminist historians, but his two choices of wife, and his support for his controversial daughter Rosa's public career, indicates that he respected independent women. While in London in 1882, he gave practical support to Rosa: he gave her £500 (£517.10 in Australian pounds; around $64,569 in 2017 values) depositing it in a bank account in her name. To do so, as a married women, she needed her husband's permission which Campbell Praed gave. TLM-P gave the money as an advance on the money he planned to leave Rosa on his death. It is significant that he did so ensuring that she had sole control of the money.23) Similarly, when his daughter Lizzie's marriage to Jack Jardine was discussed, Nora M-P stated that TLM-P intended to help them with a gift of stock, 'probably cows, branded with her name & tightly settled upon her'.24)

His will indicates that ensuring his female relatives had some independence from their husband was not an aberration. In some ways his will supports the view of him as an Victorian patriarch in that the money left to his female relatives, and some of his sons, was controlled by trustees. But, on the other hand, he made all bequests to his wife and daughters 'free from marital control', and he further emphasised that 'all payments to any female under this my Will and the share and claim of any female under my will shall be to her sole and separate use and benefit independent of the debts control and engagements of any then or future husband without power of anticipation or alienation during marriage.'25) He was being cautious - the Married Women's Property Act had only came into force in Queensland in 1891: before then, unless such stipulations were made, anything inherited (or earned) by the wife, automatically belonged to the husband. His sense of responsibility for his female relatives extended to his daughters-in-law and grandchildren, with provision being made for them on the death of his son/s. 26).

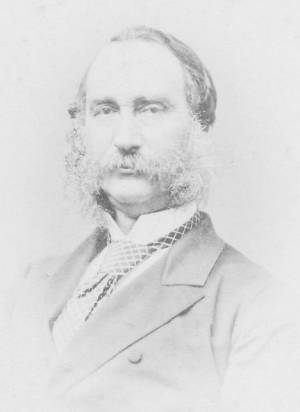

These three photos are from TLM-P's album.27) They were taken in Melbourne. The images are designed to reveal a prosperous man who has succeeded in his adopted land. For more photos of him, click on TLM-P photographs.

These three photos are from TLM-P's album.27) They were taken in Melbourne. The images are designed to reveal a prosperous man who has succeeded in his adopted land. For more photos of him, click on TLM-P photographs.

Furniture and other possessions

The beautiful furniture that TLM-P owned reveals that he shared his father's tastes for fine art and household items. The next photo is of his intricately carved Italian cabinet,28) the twin of which is in Brisbane's Tattersalls Club. It is said to have been imported to Australia by the Italian architect Mr Andrea Strombuco in circa 1885 for his home in Albion. As this cabinet is identical, and TLM-P also lived in Albion, it is assumed that it too was also imported by Senior Strombuco.29) As usual with such furniture, it neatly comes into sections:

The family has numerous examples of Australian red cedar furniture which has been passed on through the generations from TLM-P and his family. This elegant table with chairs is one example.30)

A watch which is thought to have belonged to TLM-P.31)

A watch which is thought to have belonged to TLM-P.31)

TLM-P, once he had his family's entitlement to arms confirmed, had his silver engraved. This plate is an example.32)

TLM-P, once he had his family's entitlement to arms confirmed, had his silver engraved. This plate is an example.32)

As well, a number of paintings, apart from family portraits and paintings of Maroon and district, came down the family line and were reputed to be TLM-P's. They include the following:

33)

33)  34)

34)  35)

35)

The following is a black and white photo of the original. 36)

36)

A damaged unframed painting of Hereford cattle.37) When TLM-P was in England he wrote in his diary that he had one of his late father's paintings, by Thomas Sidney Cooper, 'in the tin case for packing'. He showed it to Edmund Ashford, a former pupil of Cooper's who had watched it being painted. Ashford and TLM-P's step-sister Jemima commented that the 'the trees' in the painting made it one of Cooper's best. So it could not be this one as it has no trees. Yet the comment provides a clue that it is also by Cooper, especially as it is very like one by him of a bull's head: see Cooper painting. Alternatively, it may be by TLM-P's brother William as he had also been taught painting by Cooper.38)

A damaged unframed painting of Hereford cattle.37) When TLM-P was in England he wrote in his diary that he had one of his late father's paintings, by Thomas Sidney Cooper, 'in the tin case for packing'. He showed it to Edmund Ashford, a former pupil of Cooper's who had watched it being painted. Ashford and TLM-P's step-sister Jemima commented that the 'the trees' in the painting made it one of Cooper's best. So it could not be this one as it has no trees. Yet the comment provides a clue that it is also by Cooper, especially as it is very like one by him of a bull's head: see Cooper painting. Alternatively, it may be by TLM-P's brother William as he had also been taught painting by Cooper.38)

Colonial Masculinity

A much more problematic aspect of TLM-P's career is the connection between nineteenth century masculinity, the brutal takeover of Aboriginal lands, and the imperative to (as it was later put) 'populate or perish'. Nineteenth century Queensland was relatively isolated and sparsely populated by whites, so settlers like TLM-P idealised the land as 'vast uninhabited stretches of country waiting to be filled by resolute, hardworking Britons … Progress - conceived in the masculinist framework of aggressive expansion, ruthless destruction of the Aboriginal people, economic development and environmental exploitation - needed not only capital, brawn and sheer determination to succeed, but healthy young citizens'.39)

Historian Angela Woollacott has argued, using TLM-P as a case study, that the concept of manhood in the colonies was intertwined with acceptance of frontier violence. She unquestioningly accepts Rosa Praed's version of events despite Rosa never quite making the transition from being a novelist to that of an accurate memoirist. She also attributes TLM-P's memoir of the Hornet Bank massacre to Rosa. Nevertheless, her argument, supported by other historians, is worth considering: that 'frontier violence was accepted within evolving definitions of manhood and hence political responsibility … when we link frontier violence to gendered authority, mid-nineteenth century ideas of manhood might look a little less peaceable and restrained'.40)

TLM-P was too complicated to be a satisfactory stock figure in any historical argument, though it would be possible to mount a case that his identification with royalty, insistence on a 'courtly' bearing and even his art collection that he bequeathed to the public, was at least partly motivated by a desire to assert himself as a civilised man, and to distance himself from his part in the grim reality of wrenching land from its traditional owners.

Death

TLM-P generally enjoyed good health until the last years of his life. An exception was in August 1866 when he paid Dr Robert Handcock £1.15.0 for 'attendance on self'.41)

This is an undated photo, but shows him in old age when he was greying and had gained weight from a more sedentary lifestyle due to his illness. 42)

42)

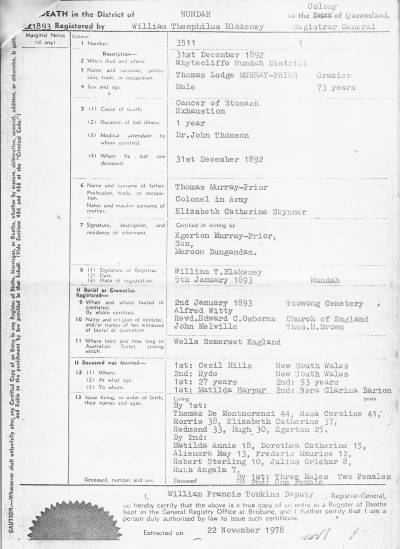

As shown in the following death certificate, TLM-P died on New Year's Eve in 1892 at 'Whytecliffe', Albion, Brisbane. His funeral notice invited his friends to attend his funeral, 'to move from his late residence, Whytecliffe, Albion THIS (Monday) MORNING at 10'clock for the Toowong Cemetery'.43).The Brisbane Courier (2 January 1893) reported that his funeral attended 'by a very large number of prominent citizens' with a hearse drawn by four horses and five mourning coaches (presumably that five were needed to fit all his family).44) The Queensland Government House flew their flag at half-mast to honour him.45)

TLM-P died from stomach cancer. While his obituary used the cliched 'he peacefully breathed his last',46) his death certificate reveals that, like so many others at the time given a lack of effective pain relief, a contributing factor to his death was 'exhaustion'. As could be expected, he had been sick some time. In August 1889 he wanted to travel to England to meet up with Nora and help her with her return trip home, but his doctors advised against it.47) Nora was overly-optimistic, writing to her daughters on 19 November 1892 that 'Father doing wonderfully well and if he goes on improving he will soon be out of danger.'48) A. G. Coventry, an unknown poet, wrote In Memoriam. The Hon. Tho. Lodge Murray-Prior, mourning him as 'Prior, the cultured gentleman, the last of that brave band/ Whose names shall be as landmarks to the children of our land.'49)

50).

50).

One cause of stomach cancer, from which his eldest son and second eldest daughter also died, is vitamin deficiency.51) Vitamins were unknown at the time. The only reference I've found so far in the stores accounts of the station ledgers (see Employees, stores) to fresh fruit and vegetables is that of 'salad oil'. Additionally, fruit trees take time to bear, vegetables could be difficult to prioritise amongst other needs, and European settlers did not value Indigenous 'bush tucker'. It is not hard to see a possible link between this early restricted diet and TLM-P and his elder children developing stomach cancer. For more on the scarcity of vegetables in the colonial diet, as well as some more ingenious adaptions, see food-on-the-frontier.

His death certificate listing his 14 surviving children, ranging in age from 44 to 7 years old.

In his will, TLM-P attempted to provide for all his family and, to modern eyes, to continue to control his family. Given he had stomach cancer, he knew he was dying, and signed his will on 5 May, seven months before he died, with three codicils dated in the weeks and days before he finally succumbed on 31 December 1892. The complexity of providing for all eventualities, and leaving money in trust for numerous dependants, meant that the trustees had to go to court to get a ruling on the will's legal meaning. This first occurred in October 1905, and then in 1940, after the death of his daughter Dorothy. The latter, to determine what would happen to her share of the trust, amounted to 10 foolscap typed pages on the legal meaning of the word 'surviving'!52) Additionally, the Trust ran into difficulties after the death of Thomas de M. M-P with the family taking the two trustees (Charles Barton and George Eddington) to court in 1905. While the step-siblings and Nora were united, the court case represented an enormous conflict for Nora as Charles Barton was her brother. As well, costs were borne by the estate.53) on 31 December 1900, his estate was valued at £66,621/10/1. In the 1930s, another great depression hit the value of the trust, but nevertheless a list of his investments as at 12 June 1931 reveals his estate was worth in total £33,683 (roughly $3,020,242 in 2017 values). This sum included an advance to Egerton of £2,275; mortgages to Julius (£2350), Meta Hobbs (£500) and Lizzie Jardine (£100) as well as the purchase of a “Mary St Property” (presumably Mary Street in Brisbane) for £11,000.54)

The estate was finally wound up with the remaining £15,500 disbursed in 1945.55)