Thomas (Tom) Prior MA

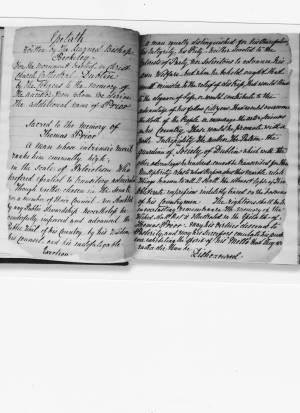

When Tom Prior died, Ireland lost a public benefactor. The inscription on his grave read:

'Sacred to the memory of Thomas Prior Esq., who spent a long life in unwearied endeavours to promote the welfare of his country. Every manufacturer, every branch of husbandry, will declare this truth. Every useful institution will lament its Friend and Benefactor. He died alas! too soon for Ireland. October the 21st, 1751. Aged 70.'1)

Today, Tom Prior is honoured in Ireland primarily for his role as the 'prime mover' in founding the (from 1820, Royal) Dublin Society in 1731.2) The Royal Dublin Society is still active, with a 'philanthropic work programme that spans across science, the arts, agriculture, business and equestrianism'.3) In the most recent booklet about Tom Prior, Teddy Fennelly describes him as the 'inspiration and driving force' behind the Royal Dublin Society's foundation. As Secretary, Tom Prior effectively 'ran the Society' for 20 years, with little 'done or achieved without his advice, help and active cooperation'. He strongly supported its system of cash incentives for agricultural and industrial innovations. The Society also actively spread its ideas through the publication of pamphlets - as they were relatively cheap and easy to distribute, they were the social media of the time. As well as writing his own papers and pamphlets, Tom Prior contributed to numerous other pamphlets published by the Society. The Society's activities were administered by different committees. Tom Prior's influence was such that he was a member of all the committees 'except accounts, and even here he countersigned the accounts fortnightly.' Fennelly further maintains that, of Tom Prior's contemporaries, there were few who 'could surpass his intellect, sincerity and courage and none who could match his compassion and his legacy of practical achievement'. His 'acute social conscience' was complemented by his being 'ever the practical down-to-earth man' when proposing reforms. His practicality was complemented by optimism. Certainly, an anonymous satire published in 1753, (A Dialogue between Dean Swift and Thomas Prior, Esq., in the Isles of St. Patrick's Church, Dublin, On that memorable Day, October 9th, 1753), portrayed Jonathon Swift as pessimistically rejecting his friend Tom's 'upbeat analysis of the Irish situation.'4)

Tom Prior was very much a product of the Enlightenment, as well as the dire conditions which prevailed in Ireland during his lifetime (see Irish context). During 1696-99, he attended the most prestigious school in Ireland at the time, Kilkenny Grammar School. He left school and, with some interruptions, was awarded a Bachelor of Arts from Trinity College Dublin in 1703. In 1712 he went to Oxford University, and awarded a Master of Arts later that year. Like many a historical person with frail physical health,5) he avoided other career options to work on what interested him most and (consequently?) lived to old age. He worked as a land agent and financial advisor but most of all, for a less exploited and more ecumenical (though still Protestant) Ireland.6) He was friendly with other reform-minded Anglo-Irish, notably the satirist author the Rev. Jonathon Swift, while he had a close friendship with the philosopher Bishop Berkeley.7). It was not entirely altruistic as Prior and his friends very much promoted the cause of their own class. They resented the English ruling class' attitude that the Anglo-Irish were inferior, and suffered from English economic policies. As well, in 1699 to protect their own wool industry, the English had passed an act of parliament prohibiting the Irish from exporting any woollen goods: that 'crushing blow for the Irish economy' ruined the Irish wool industry and members of the Anglo-Irish ruling class as well as the impoverished native Irish.8)

Throughout Britain in the 18th century, select landowners championed new 'scientific' farming methods. In Ireland, thanks to English policy, famine and diseases of poverty were constant threat. In 1740-41, it is estimated that around 912,000 Irish died of hunger, around 38 per cent of the population.9) Improving farming was literally a matter of mass life and death. 10) From 1731, Tom Prior helped promote better farming in Ireland. Of the 14 men who founded the (later Royal) Dublin Society, he was not only seen as the key founder but one who chaired its meetings and was 'its most active promoter and dedicated servant'.11) The Society's original aim was to improve Irish ‘Husbandry [agriculture], Manufactures and other Useful Arts’: very much in the spirit of Jonathon Swift's quote below.

The Society initially focused on encouraging the planting of trees as well as reclaiming the plentiful Irish bogs and mashes for agriculture. The first paper the Society considered was Tom Prior's A New Method of Draining Marshy and Boggy Lands (1731). He especially promoted greater Irish economic self-sufficiency both in agriculture and industry; another of the numerous papers he wrote for the Society was a List of Commodities imported into Ireland which could be manufactured in the Country as well as an essay on how Irish natural resources could be better utilised. He also became the authority on growing hops, used in brewing beer. His paper Instructions for Planting and Managing Hops was the basis of a highly influential treatise on hop growing. In face of the destructive English trade policies, Tom Prior strongly supported buying Irish goods rather than exported ones. In later life, he promoted growing flax and its end product, the linen industry. He published An Essay to encourage and extend the linen-manufacture in Ireland by praemiums and other means. He is credited with helping make 'the wearing of Irish linen scarves into a political statement.' 12)

Another of Tom Prior's causes was the development of skills, taking a major role in the Dublin Society teaching people how to use more efficient agricultural equipment. He did not neglect the arts, with his plan for an academy to teach drawing winning the crucial support of the Society's benefactor, Lord Chesterfield. Tom Prior's broad interests are also shown in his 1729 paper, Observations on Coin in General with some Proposals for regulating the Value of Coin in Ireland, which proposed coinage reforms to improve the Irish economy.13)

With other members of the Dublin Society, Tom Prior recognised the importance of history by founding the Physico-Historical Society. It was less successful than the Dublin Society, lasting only for around a decade.14) Tom Prior also had a role in addressing the appalling maternal and baby death rate of the time, with his support for Bartholomew Mosse in founding the (later world-renowned) Rotunda Hospital in Dublin. Tom Prior was accordingly one of the trustees of the land reserved for this innovative hospital.15)

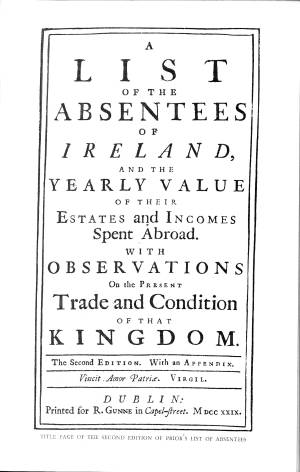

Tom Prior’s most courageous act was to publish a pamphlet in 1729, A List of Absentees of Ireland and the Yearly Value of their Estates and Incomes Spent Abroad…. It ‘pilloried his own class and many of his intimate friends’ in an effort to ameliorate the ‘appalling economic distress, and the utter wretchedness’ of the Irish. Among other things, he advocated a special tax on the minimum of £600,000 that he calculated was being taken out of Ireland each year by absentee landowners: that’s around £56.4 million in today’s values, taken from a country whose population was stalked by famine (similar policies prevailed in other parts of the British Empire, notably India - but that's another story …). While Tom Prior's claims regarding the extent to which absentee landowners contributed to Ireland's woes are now disputed, absentee landowners and their middle men contributed to the destruction of Irish prosperity. Tom Prior's pamphlet was highly influential:'one of the most important publications in 18th century Ireland and was the most reprinted; a best-seller of the day.'16)

Cover of the second edition of Prior’s List reproduced in Clarke’s Thomas Prior.

Cover of the second edition of Prior’s List reproduced in Clarke’s Thomas Prior.

No life is without misjudgement. Tom Prior's most publicised failure was his promotion of the medieval remedy tar-water, a mixture of pine-tar and water. The context of his belief in tar-water were the horrendous famine years of 1739-41: as usual, hunger has been accompanied by the plague and other diseases. Tom Prior's close friend Bishop George Berkeley initiated the public promotion of tar-water as a cure-all, publishing a pamphlet about it in 1744, lauding it as a restorative as well as cure for the plague and other diseases, both for cattle and humans. While the medical profession at the time had little success in curing disease, they did know a quack cure when they saw one. They led the attack, condemning tar-water as worthless. Prior staunchly defended it and his friend Bishop Berkeley, writing Authentic Narrative of the Success of Tar-Water, in Curing a Great Number and Variety of Distempers (Dublin/London, 1746). Alas, he was wrong: pine-tar and water was no cure for the diseases which stuck the malnourished and starving.

Prior memorials

Tom Prior was buried in the graveyard beside the Anglican church in Rathdowney. The precise location of his grave is now unknown as his tombstone was later relocated inside the church.17). His other memorials are:

1.

The Prior monument (Thomas Prior introducing Ceres to Hibernia by John Van Nost the younger), at entrance of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin. The sculpture was erected in 1756 and abounds with symbols of Prior’s work for Ireland.18) The first photo19) with me (Judith Godden) looking at it in 1985, indicates its size – around three metres high. The second photo20) is the bust of Thomas Prior on top of the monument. The effusive praise of Tom Prior on the monument was written by his friend Bishop Berkeley - in Latin. A later member of the family copied a translation into their Family Bible:

The Prior monument (Thomas Prior introducing Ceres to Hibernia by John Van Nost the younger), at entrance of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin. The sculpture was erected in 1756 and abounds with symbols of Prior’s work for Ireland.18) The first photo19) with me (Judith Godden) looking at it in 1985, indicates its size – around three metres high. The second photo20) is the bust of Thomas Prior on top of the monument. The effusive praise of Tom Prior on the monument was written by his friend Bishop Berkeley - in Latin. A later member of the family copied a translation into their Family Bible:

2. Perhaps the most recent monument to Tom Prior is the one recorded by the Laois Heritage Forum: In 2017, the Forum stated that in 2016, at St Andrew’s Church of Ireland, the Square, Rathdowney, a plaque was unveiled in Thomas Prior's memory, not just as one of the founders of the Royal Dublin Society, but also as the founder of the (local) Ossory Show.

3.  This photo of a bust of Tom M-P was taken by Nora Boyd when she visited Dublin. Presumably it is the one that was sculptured for the Dublin Society by John Van Nost the younger, who created Prior's memorial in Christ Church Cathedra.21)

This photo of a bust of Tom M-P was taken by Nora Boyd when she visited Dublin. Presumably it is the one that was sculptured for the Dublin Society by John Van Nost the younger, who created Prior's memorial in Christ Church Cathedra.21)

4. Tom A. M-P recalls another statue of Tom Prior in a chapel opposite Trinity College – a quest for the next person who visits Dublin?

5. Another memorial is the Thomas Prior Hall, in the Dublin suburb of Ballsbridge. The building was purchased by the Royal Dublin Society in the 1970s and subsequently renamed Prior House.22) It was later sold and, as at March 2018, it is part of Clayton Hotel. Only the front of the original building, with its name, survives.23)

(Above) Photo of J. Godden in front of Thomas Prior House, August 1985.

Death and founding the Murray-Priors

Tom Prior died after, as it was described at the time, ‘a tedious fit of illness’. He was ‘not a wealthy man’ because he was ‘one of the few who sought neither place, patronage not honour’, and worked entirely voluntarily for the Dublin Society. When his friend Bishop Berkeley wrote his eulogy, he described (in Latin) Tom Prior as ‘not too careful of his private fortune, since he took a singular interest in the benefits of his fellow citizens’.24) Certainly the home in Rathdowney, Garrison House, where he was born and died, seems modest enough even remembering that he also had a town house in Bolton Street, Dublin.25)

Photo of Garrison House, courtesy Laois Heritage Forum. It is described as located just off the Square in Rathdowney.

Photo of Garrison House, courtesy Laois Heritage Forum. It is described as located just off the Square in Rathdowney.

When Tom Prior contemplated possible heirs, there were no males who were clear contenders. His brother Richard appears to have died, leaving two step-brothers from his father's second marriage to a possibly disreputable woman (given that the marriage was reputedly kept secret). Of these step-brothers, Robert Prior was considered a 'good' man but not his son John, while the other step-brother, William, 'eclipsed them all' in bad behaviour. The morally upright Thomas passed over these possible heirs because of their ‘riotous living’ (apparently more on towards the disgraceful rather than mere fun-loving point on the behavioural spectrum). Instead, Thomas left the Rathdowney estate to his cousin John Murray, the son of his aunt Mary Prior (sister of Colonel Thomas Prior) who had married the Reverend Thomas Murray. The family lived at Rathdowney and were close to Tom Prior.26) In Thomas’s will dated 22 June 1751, his legacy was conditional on John Murray adding ‘Prior’ to his surname, hence ‘Murray-Prior’ was born.27)

The Murray family

At this stage, no more is known about the Murray family – a challenge for you to find out more! Though, as historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich wrote, 'well-behaved girls seldom make history', and it is sadly true that a family that produced a well-behaved clergyman's son is likely to be far less interesting than one with sons disinherited because of their 'riotous living'. As well, the long conflict for Irish independence means that a lot of family records have been destroyed by misadventure.

Sources: John & John B. Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland: M to Z, London: Henry Colburn Publisher, 1846, p.1075; Clarke; Family Bible; Teddy Fennelly, Thomas Prior: his life, times and legacy, 2001.