This is an old revision of the document!

Rosa Caroline Praed, nee M-P

Rosa (or Rosie as she was called by her family) as a young adult.1)

Rosa in 1888.2)

The State Library of NSW has this portrait of Rosa Praed painted by Emily Praed in 1884; it may be a copy of one painted by J.M. Jopling that year. In 2019, it is in the State Library's portrait gallery on open access:

The themes of Rosa's writings were confronting for her contemporaries: 'the young colonial woman's encounter with metropolitan political and literary culture, the 'tragedies of the sexes', the horrors of frontier conflict, and the exploration of psychic and spiritual life.'3) Especially in the 1890s, Rosa was accused of promoting immorality through her more realistic novels, and at least one play, featuring domestic conflict and the plight of women, brought up to be 'innocent' (Rosa would say 'ignorant') and thrust into marriages they had little hope of escaping. These accusations would have been even more strident if her publishers hadn't insisted on bowdlerising her work. Patricia Clarke points out that Australian critics were particularly critical of Rosa's writings as too risque.4)

Given Rosa's notoriety, especially in this era when any publicity threatened a woman's status as a 'lady' and her entire family's claims to gentility, it is noteworthy that she always had her family's support, including that of her conservative father who put so much effort into reclaiming his family's gentry status. In 1880, for example, when TLM-P planned to visited 'home', England, an important aim was to see Rosie.5) A number of her books now in public libraries or offered for sale have affectionate inscriptions in them indicating they were gifts from Rosa to her family.6) One of the last of her books acquired by her father was a special printing of only 230 copies: TLM-P received his copy on 13 March 1890. The book was a loving tribute to the Thames, called The Grey River, and written with Rosa by her friend and collaborator Justin McCarthy, with illustrations by Mortimer Menpes.7) The support she received extended to her wider family - she inscribed on her book The Luck of the Leura, 'To Dr. Lightoller Gratefully acknowledging “The Doctor's Yarn” RM Praed.'8)

TLM-P's support for Rosie's writing was firm but considered. When he visited her in May 1882, Rosie told him about latest book (her 3rd): 'much interested in it and think it wonderfully written far surpassing anything she has done yet, but must think over it … I went to bed full of her last [book] and was going over it for a long time both before and after sleeping'.9) Rosa's biggest problem was not a censorious father, but one brimming with enthusiasm for her writing and who wanted to help. He also had an understandable desire to protect her from the ramifications of accusations of immorality: 'en route I resumed my sequel of Rosie's story, going into life's feelings and what I would like under these circumstances to happen …would not in my opinion injure the story but would improve it and remove any criticism from goodie goodie people, mine made an interesting sequel. I hope she will adopt it or something similar.'10) The book was Nadine, one that Chris Tiffin considers marked Rosa Praed's 'growing imaginative independence from Australia in that it is entirely set in Britain. Reflecting the contemporary interest in aestheticism, it concentrates on the psychology of a woman who craves excitement, oscillating between elation and extreme depression. Although courted consistently by a stolid lover, in pursuit of sensation she becomes pregnant to a second man, and eventually marries a third, a corrupt Russian prince living in an exciting but morally brittle world. The novel’s success was increased by the open secret that the heroine was based on Olga Novikoff, the so-called “M.P. for Russia”, who was closely linked with [Prime Minister] Gladstone in the 1870s and 1880s. It was this novel which established Praed as a successful writer in the British market and which launched her socially.'11)

By July 1882, when TLM-P was staying with Rosa in England, she discussed the plot of her 4th novel with her father who concluded 'that I think it will be very good'.12) Moloch: A Story of Sacrifice was published in 3 volumes in 1883. The draft plot was daring for the times and one she had to censor for publication. Chris Tiffin summarises it as, 'the young woman marries a cad only to discover that he has previously eloped with her mother and had two illegitimate children by her. … This plot … would have given the reviewers apoplexy'.13) TLM-P had no such reaction. When he read the draft volume I, he concluded it was 'well written and forceable'. He did not 'see anything objectionable … gave opinion to writing a preface & small alternations'.14) The next day he started on Volume II, finishing it in bed that night. He was enthralled: 'So far it is well written, I think the best of Rosie's, the interest is intense…. It got a great hold upon me and I could not sleep but spent a restless awestruck night.' He sympathised with the heroine: “the more I thought the more dreadful (awful) Generras['s] position'. His concern was that the public would not understand Rosa's aim: 'No doubt the book would create a great sensation and taken as meant would do good, but the majority could not understand'. He suggested to Rosie that the heroine discover the truth in time for her to call off her marriage, and 'after a long time' she might marry her first love. 'The plot would not be so intense, but the objectionable part would be taken out and the book be still made to follow out the intention of the author. … Will Rosie see it as I do?'15) He thought that she did. The next day, he 'settled down to read the 3rd vol.' and talked about the novel to 'Rosie who agreed with me and had had the same said before. She sees her way to make the alteration proposed and otherwise she thinks [will] improve “Moloch” without much trouble and have it ready for next February.'16) His support for Rosie shows in other ways, including going with her to her publisher, and helping her move house when the Praeds moved to London.17)

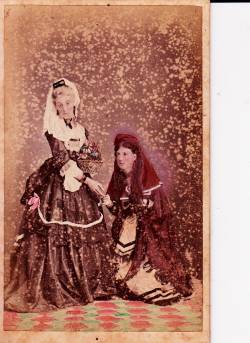

Photos of Rosa are largely missing from Nora and TLM-P's albums, most likely given to Colin Roderick when assisting him to write his biography of Rosa. The following damaged one from the latter album is labelled 'Rosie Prior & Lizzie Jardine (Mrs Wilbraham)'. The Lizzie Jardine here is John Jardine's sister; Wilbraham was her married name. When Lizzie M-P married John Jardine the two Lizzies became sisters-in-law.

Rosa's husband was the ambitiously named Englishman, Arthur Campbell Bulkley Mackworth (known as Campbell) Praed. In the late 1880s/early 1890s, they lived in the prestigious locality, 16 Talbot Square, Hyde Park, London.18) The next photo from Nora M-P's album appears to be of Campbell Praed. He did not retain his youthful good looks: when TLM-P visited the family in 1882, he recorded that Rosie looked 'better than he expected, though worn' while Campbell was 'very stout weighing 15 stone'. This was an exaggeration -later TLM-P recorded that Campbell weighed himself and was 13 stone 5lb.19) TLM-P was especially delighted with Rosie and Campbell's boys whom he described as 'fine healthy little fellows … boys splendid'. As he mentions only two boys, it is likely that they were the younger ones, with the eldest at boarding school. Campbell had his brewery nearby which he was then expanding to include aerated water and other drinks.20)

He did not retain his youthful good looks: when TLM-P visited the family in 1882, he recorded that Rosie looked 'better than he expected, though worn' while Campbell was 'very stout weighing 15 stone'. This was an exaggeration -later TLM-P recorded that Campbell weighed himself and was 13 stone 5lb.19) TLM-P was especially delighted with Rosie and Campbell's boys whom he described as 'fine healthy little fellows … boys splendid'. As he mentions only two boys, it is likely that they were the younger ones, with the eldest at boarding school. Campbell had his brewery nearby which he was then expanding to include aerated water and other drinks.20)

Rosa and Campbell Praed illustrate the popular saying about marrying in haste and repenting in leisure. They had four children, after which they they lived together, but considered the marriage over. Nevertheless, Praed encouraged and supported Rosa with her career as a writer. She only left him in c.1899-1900, a year before his death, to live with spiritualist Nancy Harward. Rosa believed she and Nancy were re-incarnated 'twin souls', destined to be together in succeeding lives: a more sceptical modern view is that Nancy's memories of 'past lives' derived from schizophrenia. Despite her spiritualist belief, and perhaps influenced by Justin McCarthy, in 1891 Rosa formally converted to Catholicism. She later changed her mind. Before her death in 1935 she drew up a codicil to her will asking to be buried with Protestant rites in All Souls Kensal Green Cemetery, London, sharing the grave of her companion for so many years, Nancy Harward.21)

Rosa and Campbell Praed's children

All four of Rosa's children predeceased her. The life of her only daughter, Maud, was especially tragic. It is no wonder that Rosa took to the popular fad of her era, spiritualism.

1. Matilda (Maud) Elizabeth Mackworth Praed (1874-1941), born 8 February 1874 at Rosa's family home 'Montpelier'.

Rosa Praed and her daughter Maud, aged ten months, Rockhampton, ca 1874, QJO.

Rosa Praed and her daughter Maud, aged ten months, Rockhampton, ca 1874, QJO.

Maud was known as clever and also appears to have been a talented artist - there is an attractive watercolour landscape in the NLA with a note on the back that it was 'Maud's'.22) She was also profoundly deaf, a disability that Rosa blamed on her syringing Maud's ears when she was a baby.23) Mother-blame was strongly assumed when a child had health problems, and in one of her novels Rosa writes, 'My little girl is almost an idiot. She is deaf and dumb. They said - they said that it was because I had been unhappy [when pregnant]. I have suffered - I can't speak of it.' Later Rosa came convinced that Maud's suffering and later violence towards her was due to Rosa's sins in a past life in ancient Rome.24) The reality was likely to be much more prosaic; that Maud's deafness was caused by measles or scarlet fever.25)

TLM-P visited 'poor dear little Maudie' when she was 8 years old and living in an institution which taught deaf children through lip reading. He described her as 'a nicely made little lady, with very quiet manners and an intelligent look… black eyes bright and loving and thick brown hair.' At this stage she was very loving to her mother. Seeing her and the others struggle to talk 'made poor Rosie and me sad, but Maudie is a darling little creature'.26)

In his will TLM-P tried to ensure Maud's future by stipulating that his legacy to Rosa would go to Maud on her mother's death. As with the other women legatees, this was to be 'free from marital control'. Maud was admitted to a private mental hospital in Bournemouth in 1900; tragically she remained committed within a hospital for the rest of her life, over 40 years. She died on 6 July 1941.27) As Jessica White so eloquently writes, for Rosa the pain of her daughter's fate could not be expressed in writing: 'Rather, it could be heard only through a thunderous silence.'28)

It is unfair, but Maud Praed's life seems all the more tragic given she was, as shown here, a beautiful young woman.29)

It is unfair, but Maud Praed's life seems all the more tragic given she was, as shown here, a beautiful young woman.29)

The hospital case book for Maud suggests that she became paranoid after the death of her beloved father. On 28 September 1902 her hospital the notes stated that 'She informs me she is accused of killing her father & that the police are spreading reports of scandals about her - she cannot sleep & wishes to escape from the persecution'. She could lip-read and read writing, but could not speak very intelligibly, and suffered from various paranoia delusions and hallucinations. In April 1907 she was transferred to the private asylum St Ann's at Bournemouth.30)

Maud's story has recently inspired a 'creative non-fiction' book by Jessica White titled Hearing Maud (UWA Publishing, 2019).

2. Bulkley Campbell Mackworth Praed (1875-1931), born 6 December 1875, less than two years after Maud. Rosa, like her step-mother, did not welcome getting pregnant on virtually a yearly basis, with Nora writing to her that 'I am sorry at the hint you give of future expectations but you could not expect to go scot free'.31) By the time Bulkley was born, the Praeds had abandoned their struggle to make a living on Port Curtis Island, and were living at Rosa's family home 'Montpelier'. Bulkley's birth certificate has one of the witnesses to the birth as 'Mrs Prior (Nurse)' - Nora?32) Buckley was the stereotypical responsible, sober eldest son - until he could take no more of the chronic, intense pain of terminal cancer. To end his suffering, Bulkley shot himself on 29 April 1931. Typically, Rosa saw herself as central, wondering what impact it had on him that, while she was pregnant with him, she was extremely distressed because baby Maud was 'so near death'.33)

3. Humphrey Praed (1877-1904), born in England, 9 May 1877. As was common for younger sons, he was sent to outposts of the British Empire to make his living. After an unhappy time in Western Australia, he moved to California where he was an assistant manager for a company that owned orange groves; he also bought his own orchard. He was a talented sportsman and a playboy: on 20 November 1904, taking an actress for a drive in his sports car (with his chauffeur in the back seat) in the early hours of the morning, there was an accident, and he died 'almost immediately', aged 24.34)

4. Geoffrey Praed (1879-1925), born in England, 19 December 1879. According to Roderick, he was the black sheep of the family. He ran away and enlisted to fight the Boers in South Africa; the family subsequently brought him home, provided him with an army commission and sent him 'to India to learn to be a soldier and a gentleman'. It is not sure if they succeeded, but he did prove to be a talented linguist so, against his will, was retained in India during the First World War until repatriated to England when he became ill. After the war, with a Major's pension, he returned to South Africa with the aim of becoming a big game hunter. He died in Rhodesia in September 1925 after a rhinoceroses, not appreciating that Geoffrey was the hunter and not the prey, charged and fatally wounded him.35)