This is an old revision of the document!

Nora M-P nee Barton

Nora and TLM-P's Children

1. Matilda (Meta) Aimee, 25 September 1873 - 18 August 1939.

2. Emmeline Mary, 18 May 1875 - 5 February 1876.

3. Dorothea (Dorothy) Katherine, 13 December 1876-2 January 1941.

4. Alienora (Eileen) May, 31 May 1878 - 1955.

5. Frederic Maurice 9 March 1880-1956.

6. Robert Sterling, 29 August 1881 - 31 May 1962.

7. Julius Orlebar, 25 March 1884 - 6 October 1931.

8. Ruth Angela, 27 July 1885-15 August 1961.

Nora was step-mother to the eight children who survived from TLM-P's first marriage to Matilda Harpur and, as shown above, eight children of her own. She presents as a loving step-mother and mother. It is significant that the level-headed eldest son of the family, Thomas de M. M-P, appreciated his youthful step-mother. One piece of evidence is a two-volume book by the explorer Henry Stanley,1) which he gave to Nora with, as he wrote in them, his 'best love'. Nora also demonstrated her goodwill when she named her first daughter Matilda. Her choice of second name Aimee (meaning beloved) could apply to both Matildas.

Nora's eldest step-daughter, Rosa Praed, was only five years older, and they became close friends, bonding over common interests including a distaste for constant childbirth and a love of literature. It is probably no coincidence that, a year after Nora did so, Rosa also called her first-born Matilda. They corresponded regularly and intimately, with 66 of Nora's letters to 'My dearest Rosie' surviving - sadly Rosa's to Nora haven't survived. Nora and Rosa were both interested in the women's movement. A play written by Nora was partly about an 'Admission of Female Members [of Parliament] Bill': Professor of English Colin Roderick commented that, while only part survives, 'her talent is clear'.2) Though interested in women's rights, and keen that her daughters have more options than marriage, Nora was no radical. She wrote to Rosa that:I feel so certain that the nineteenth century will not stand such iniquities much longer than every time I go on a voyage I feel (as) a man might do who was going to have his leg cut off in the year before chloroform was invented & who foresaw the invention.. Til I get my cabin to myself I don't mean to agitate about my vote or my seat in parliament - which I can get along very well without'.3)

Neither woman wished for more than one or two children, with Nora writing:'Though I can well understand your not wanting any more [children] & trust fervently that if my No. 2 arrives safely, it may prove the last, my precious little Meta flourishes & grows more lovable & clever every day.' Nora's love for Rosa was passed on to her young daughters when they all lived in London. Ruth, her youngest daughter, also wrote to 'Dearest Rosie', signing herself 'Your loving sister'. She was among the family to welcome Rosa's gifts of her latest book, no matter how controversial.4)

Nora was highly distressed with yearly pregnancies, having she wrote to Rosa, a 'morbid horror' of large families.5) Given given the pro-natalist environment she lived in, it is not surprising that, while she considered 'people with large families are much to be pitied', she was 'not sure' that 'they who have none are not even worse off'.6) Similarly, she tried to ruefully accept child-bearing as her 'mission' in life, in order to 'replenish the land'.7) Certainly, she have reason to be wary of drastic measures, telling Rosa that she knew a woman who 'tried to abort her baby … killed herself in the process.8)

Her despair at her repeated pregnancies probably went beyond pure logic, but one reason was that each additional child she had detracted from TLM-P's ability to establish his existing sons with property or a profession of their own or to provide an income for the daughters (despite Nora's own example, earning their own living never seemed an option for any of the daughters). All the evidence is that she was a loving mother, and flippant comments should not be taken out of that context, as in a letter to her husband from Lausanne in 1888, that it was a matter of 'great self-reproach & sorrow to me that I should have brought into the world so many children to share the small means. I could dispense with the five youngest with happiness'.9) She was not alone in making such comments in this age of profile child-bearing. The novelist Charles Dickens, for example, wrote in reaction to the birth of his tenth child, that 'on the whole I could have dispensed with him'.10)

Nora's confiding in Rosa was probably the only outlet she had to comfortably express her concerns about so many children. The women of Boonah district around Maroon had a very similar fertility pattern. Although Nora was 5.5 years older than the average bride, she became pregnant immediately and had more children than the average woman. Nora had 8 children in 13 years. The district average was 7.76 over 16 years; rural (white) Australia's average number of children was 5.79 and nationally the average was 5.31 children.11)

A factor in Nora's attitude towards her pregnancies was that childbirth in Queensland was highly dangerous, more so than in Europe or the southern colonies. Nora's fear of dying in childbirth was well-founded. In 1878 the maternal death rate peaked at one mother dying for every 188 live births - and this figure excludes later deaths from birth injuries. For most of Nora's child-bearing years, her chances of dying in childbirth were around 1:200.12) In Queensland in 1875, 55.2 mothers died for every 10,000 births; in 1885 the figure was 59.1:10,000 births.13) Additionally, the chances of the baby dying was high: in 1857, nearly 10.5 per cent of infants died (excluding indigenous births).14)

Nora's modernity also showed itself in her rejection of pain in childbirth. For numerous reasons, pain had traditionally been seen as beneficial.15) Dr Henry Lightoller, a grandson of Matilda's sister Rose Haly, had an opposing attitude. Nora M-P strongly disapproved of his refusal to offer pain relief in childbirth, even to his own wife Minnie who had a deformity which meant childbirth was agonising. The only time he allowed Minnie chloroform was when he needed to use instruments to birth the baby. Nora, as she wrote to Rosa Praed, considered 'Dr Lightoller is a staunch opponent of Chloroform tho' his chief argument against it seems to be the cowardice of taking it which I think is a question for the sufferer to decide, and could not help telling him what I felt keenly, that were it a misfortune to which both sexes were liable chloroform would have been given years ago. He looked astounded at my venturing to discuss the subject, looking on it as becoming in a man and a doctor to lay down the law – for women ‘theirs is not to reason why – theirs but to suffer and die - a view of the case against which I, as one of the suffering class, protest vehemently. He is a good little dogmatic man, skilful in his degree and he has the best wife that ever trod shoe leather - but I wish she would no be so submissive as regards chloroform.’ Nora went on to say that Minnie told her 'that she had been 12 hours in the most fearful agony, at the end of which they had given her chloroform which had brought it on so they could use instruments'. Nora's view was that she 'would want to know a very good reason why before I would suffer like that in deference to my husband's general principle and it stands to reason that she would recover better if she were not so long ill and in pain'. She was indignant that Dr Lightoller had made Minnie promise not to expect chloroform unless it was necessary for him to use instruments.16) The reasons for Dr Lightoller's reluctance to use chloroform was influenced by the common religious view that women were ordained since Eve to give birth in pain, and/or concern about its safety. It was also in keeping with the general reluctance of Brisbane Hospital doctors to use anaesthetics even for amputations and other major surgery even years after its use was routine elsewhere.17)

Nora did not live with many of the rights we now take for granted, including control over her own children. After TLM-P's death, her brother Charles Barton was one of her trustees; it was her trustees who, as Charles bluntly told Nora, were responsible for her young children. Given gender divisions, he considered he knew best when it came to her sons. In 1896, four years after TLM-P died, he informed Nora that her 'boys are acting the goat in Brisbane … they being boys [are] full of nonsense spirits are kicking over the ropes'. With the youngest 10 years old, they were, he insisted, getting beyond her control and should be sent to a good boarding school; he suggested Ipswich. He then appealed to her maternal concerns: that it was 'a matter of supreme importance that your boys should get every advantage.' He was not advising something he would not do to his own children: he'd just sent his three daughters to boarding school and as soon as his sons shed their milk teeth, 'off they go too'.18) Nora had little choice, but accepted his advice.

As far as her daughters were concerned, Nora was radical and utterly determined that they would not be financially constrained to marry. In one of a number of similar statements, she replied to Rosa's query 'how I am going to get them husbands. I am going to bring them up to be happy old maids. If the husband comes, well and good - but if he does not come, they shall not feel their lives wasted and spoilt. Nor will they take the wrong man as better than none. They are to be taught cooking and sewing and all household accomplishments, be thoroughly versed in modern languages and be put in the way of reading and enlarging their own minds rather than crammed with facts.'19)

All the seven surviving children of this second marriage shared equally in a bequest of £28,000 in their father's will. The income from this bequest was substantially less than TLM-P would have hoped because, when he died, Australia was experiencing a severe depression and then suffered from a prolonged drought. As well, his estate had to absorb a significant loss of money on the Aberfoyle property. By 1905, the interest on their £4,000 each earned them £72 p.a. - or around $10,809 in 2018 values.20) This was fine for the sons as it added to their income; less so for the single daughters who did not earn their own living and had to rely on their mother's financial support.21)

For more details of these children and their descendants, click on the sidebar entry.

Visit to Europe, 1885-89

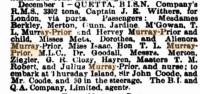

On 1 December 1885, TLM-P, Nora, Lizzie Jardine, Maggie M-P with her little son Hervey, Meta, Dorothea, Alienora, Robert, Julius and his nursemaid, all departed for London on the steamship Quetta.22)  Nora and her children stayed overseas until late 1889, with quite some time spent in Switzerland.

Nora and her children stayed overseas until late 1889, with quite some time spent in Switzerland.

The following three Swiss scenes were likely to have been bought as souvenirs when Nora lived in Switzerland. The first is of a famous waterfall seen on the way to Jungfrau.23)

In August 1889, Nora heard that TLM-P was ill and wrote back saying that she had advertised the lease on the apartment they were living in at Lausanne, sold their furniture and was planning to return to Australia asap.TLM-P wanted to travel to England to meet up with Nora and help her with her return trip home, but his doctors advised against it. Instead he sent £500 to her for expenses. Nora, 7 unnamed members of her family, and an unnamed governess and servant arrived in Sydney on the Oceana on 21 February 1890. Nora and just three of her children, governess and nurse (all unnamed) left Sydney for Brisbane on the Maranoa on 3 March.24)

Widowhood, Travel and Old Age

Nora was widowed in 1892, when she was 46 years old. She was to survive her husband for almost 39 years, but never remarried. At some date, probably in the 1890s while mourning in her early widowhood, Nora chose lines from poetry to describe family members. Those she chose for TLM-P were from Tennyson: 'Whatever record leaps to light/ He never shall be shamed.' For herself, she chose two extracts, both suggesting she was grieving for TLM-P. The saddest quote she chose was from Longfellow: 'My thoughts still cling to the mould'ring past/ but the hopes of youth full thick in the blast/ And the days are dark and dreary.'25)

Under the terms of her husband's will and codicil, Nora could remain in their Brisbane home Whytecliffe and also a recently furnished cottage in Sandgate, a coastal suburb of Brisbane. She was to have at least £500 p.a. to meet the cost of any of her under-age children living with her.26) In 1904 her trustees wrote to her that her income from TLM-P's estate had declined by 20 per cent, so that she received £123.12.0 [presumably a month, but possibly a quarter?] (in 2017 values around $18,719)27)

Despite the provision in her husband's will that she could stay in their Queensland homes, Nora moved to Sydney. Perhaps she wanted to be closer to her mother and other family; perhaps Whytecliff with its 22 rooms was too big for her.28) Nora's two single daughters, Dorothy and Ruth, and younger sons Robert and Julius, went with her. They returned to the Gladesville area, close to where Nora's widowed mother Emily Mary Barton lived.29) Nora and her daughters were close, and Nora was an explicitly loving mother. A letter to her 'dearest daughters', for example, ended with 'dear love to you both, I am ever darlings, Your loving Mother Nora C. Murray-Prior.'30) From at least November 1900 to 1904, Nora, her two single daughters Dorothy and Ruth, and her son Julius, lived at 'Karlite' (also spelt Karlyte), a house on what is now Victoria Road, Gladesville. It is possible that she was renting from Gerald Herring who at one stage owned 'Karlite'.31) Four years later, her second youngest son Robert married Gerald's daughter. From 'Karlite', by June 1904 Nora and her daughters rented a beautiful, sprawling sandstone home,'Oatlands' at 10 Ferry Street, Hunters Hill.32)

'Oatlands' in June 2023

'Oatlands' in June 2023

Some time later, at Ruth's insistent urging, they travelled to Europe. Ruth acknowledged that they would have to live quietly and cheaply and 'chase the climate as we do here.'33) By January 1913, they were in Rome with Mabel M-P (see sidebar, Mabel was Nora's step-grand-daughter) and all learning Italian. Over a year later, in April 1914, Nora and her daughters were in Heidelberg, Germany. That city was, Ruth wrote, 'a dream of loveliness', but it would only be three months before the Kaiser swept it, and most of the world, into war.34)

With the outbreak of World War I, they lived in England in various private hotels and rented places; Nora was to live in London (by 1919, in Highgate) for the rest of her life. In 1928, a letter from Rosa Praed gives their address as 3 Gresley Road, off Whitehall park, Highgate. N London.35) It appears that by 1918, when the war ended, she was considered too ill to travel. In 1915, Dorothy described her mother in terms that suggested she was an invalid: we 'just had Mother tucked up' in bed when there were bomb explosions: when they put up the blind in Nora's bedroom they saw one of the dreaded Zeppelins glide past. 'Mother', Dorothy wrote, ' was as calm as a cucumber - just lay in bed watching the Zeppelin.'36)

During the war, probably for the first time in her life, Nora lived - at least for a time - without help from a servant. Nevertheless, she contributed to the war effort by billeting soldiers in her home, and helped to support them in other ways.37) Ruth wrote to Rosie Praed that the men didn't talk much about their experiences except for one man fresh from Flanders and visiting with his wife and children - he told Nora about the women and children maimed and killed, 'His eyes looked mad almost & he clutched at his own child as he spoke in such a wild way …'.38)

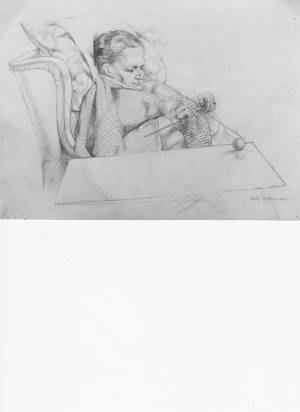

Ruth gave more details of Nora's wartime life in March 1915: they had had eight years of living in various boarding homes, with Nora unwell and essentially house-bound by the time of the war. Ruth was 30 years-old and spirited, so it is understandable that she was bored: she and Dorothy reading the newspapers to Nora in the morning; more reading and knitting in the afternoon, '& always there is bridge in the evening til a late hour. Monotonous!'39) Evening bridge appeared to be a family habit. There is a transcript of a poem written by Nora S. Barton in December 1914, entitled 'Family Bridge at Truganini', extolling the joys of her nightly game of bridge. Nora Sterling Barton was Nora M-P's niece. 'Truganini' appears to be the name of the house - that it was named after the ill-fated Truganini is a clear indication of Tasmanian connections. It was possibly associated with the Graves family, strong supporters of Truganini. 40)

One of Nora's health problems was her eyes. As far back as 1884, she wrote to Rosa that her eyesight was rapidly deteriorating.41) By 1915, she had been blind in one eye for a long time. Ruth explained that Nora's doctor was urging her to consent to him operating on her eye 'again', hoping that would secure the sight in her good eye. The operation involved having her eye removed and replaced with an artificial eye, an idea that Nora understandably found repugnant.42) Nora had the operation and put on a brave front. Her nephew Max Barton wrote to his mother in 1915 that 'Aunt Nora looked splendid and was in great form, you could not tell the glass eye at all unless you were in the know' and 'Aunt Nora is ever so much better since her return from Hospital and has quite got back all her old wit.' 43) Despite the operation, Nora had constant problems with her remaining eye. Her sight faded, so that by October 1922, she was blind. Rosa Praed wrote of her admiration at the fortitude which Nora met adversity.44) It was perhaps some comfort to Nora that her niece Emily Paterson, who was blind from a young age, had forged a successful life for herself, initially from Nora's old home of Rockend at Gladesville. Emily Paterson's key achievement was founding Australia's longest-serving mental health service, Aftercare, now called Stride.

The following sketches are of Nora in 1929 when she was 83 years old; they are by her great-niece Isabel Huntley. She died two years later, at home in Highgate, London45) - released from suffering after years of illness.46)

47)

47)