This is an old revision of the document!

Matilda Murray-Prior and her children

Matilda (1827-68) was TLM-P's first wife and the second daughter of Thomas Harpur of Cecil Hills near Liverpool (now western Sydney).

The only known photo of Matilda.1)

The only known photo of Matilda.1)

Matilda's family came from a Northern Ireland. She was born 'in the parish of Desertcreat, near Tullyhogue, south of Cookstown, a Protestant plantation town in the northern Irish county of Tyrone.' Her mother, Rose or Rosa (nee Adams) died in 1835. In after years, little was known about her: TLM-P stated 'unknown', when required to give her Christian name on his wife's death certificate (see below).2) Another son-in-law gave her name as Rose though Patricia Clarke thought it was Rosa.3) After the death of Matilda's mother, Patricia Clarke states that the family moved to Dublin. There Matilda's father married Mary Jane Speer, whose father was a Dublin solicitor.4) Before they emigrated, Matilda and her family gave their address as Lime Park, County Tyrone and College-square North, Belfast.5) To emigrate, 'They travelled to the English port of Plymouth and, on 24 June 1840, left the United Kingdom aboard the newly built barque the Lord Western under Captain Lock.6) They arrived in Sydney on 5 October 1840, a year after Matilda's future husband.

The Lord Western's passenger list7) reveals that the Harpurs sailed with 233 'bounty emigrants', that is, people who emigrated with the assistance of money from the Colonial Government. The Harpurs, like TLM-P, were 'cabin passengers', paying their own way in superior accommodation. As well as 'Miss Matilda Harpur' and her father and step-mother 'Mr. and Mrs. Harpur', there was an elder and younger brother along with two sisters: 15 year-old Thomas Harpur,8); Miss E[lizabeth] Harpur9); Miss Rosa Harpur10) and 9-year-old Master A.H. Harpur.11)

Thomas Harpur first tried farming on the Parramatta River, then settled in Cecil Hills, north-west of Liverpool.12) His and Mary Jane Harpur's daughter Emily Anne was born in 1843.13) The birth notice inserted in the paper gives scant recognition to Mary Jane: it simply states that 'On the 4th instant, the Lady of Thomas Harpur, Esq., of Cecil Hills, of a daughter'.14) Like her step-sisters Matilda and Elizabeth, Emily married and lived in Queensland.15) Matilda's step-mother, described as Mary Jane Harpur nee Speer, the widow of Thomas Harpur late of Cecil Hills, died in London in 1887. Only one offspring was mentioned: Richard Harpur of Barmundoo, Gladstone.16)

Thomas Harpur was not a success in the new colony. His granddaughter Rosa Praed was an imaginative novelist rather than reliable biographer. Nevertheless, she drew on her mother's letters when she wrote that Thomas Harpur was unsuited to the life of a colonial bushman. Rosa quoted Matilda writing to her fiancee as bemoaning that their property was plagued by drought and bushfire while “Papa, while his bush is burning and his beasts are perishing, sits in the little parlour writing poetry… He is now writing a piece on Life which is very pretty, but mama does not like his confining himself so much to the little parlour, for besides injuring his health, poetry also makes him neglect the station. But papa, she mournfully adds, was never cut out to be a bushman; he is much fonder of writing poetry than of riding after cattle.”17) Thomas Harpur's poetry appeared in a Sydney Weekly called Atlas under his pseudonyms 'Harmonides' and 'Cecil Hills', and in 1847 his major epic poem, A Land Redeemed, was published.18)

Whether because of his neglect of his property in favour of poetry or another cause, by May 1844 Thomas Harpur was bankrupt. He even had to hand over his clothes to his creditors.19) In 1846, in a flowery letter defending himself against the charge of providing 'sly grog' (home-made alcohol) and noting he was acquitted of the charge, he described himself as a 'farmer'.20) He, his wife, and two younger children had a lucky escape that year: the house caught on fire and when fighting it, a large chest was dragged from the fire, then was discovered to contain gunpowder. Thomas Harpur had brought it out 'from home', and forgotten about it! Note in this account, only two of his younger children are mentioned: had the others all left home?21) Thomas Harpur was still living at Cecil Hills in 1847.22) He died in 1848, aged 51.23)

Given her father's love of poetry and lack of desire to tackle alternative employment, it is understandable that numerous writers have assumed that Thomas was the brother of the prominent colonial poet, Charles Harpur. Additionally, Matilda also was a talented writer, though her talent was used mainly used to educate her children to appreciate English literature and history. Charles Harpur, like Matilda, was also to die of tuberculosis.24) However, a shared surname appears the only traceable family connection.25) Certainly none of those who assert that Charles and Thomas Harpur were brothers have provided any evidence of the supposed relationship. Thomas Harpur was born in Ireland in 1797, migrating to Australia in 1840; Charles Harpur was born in Australia in 1813. His parents were both convicts and married in 1814: his father, who had been a school master, was transported for highway robbery in 1800.26)

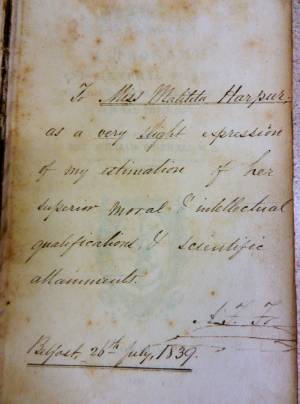

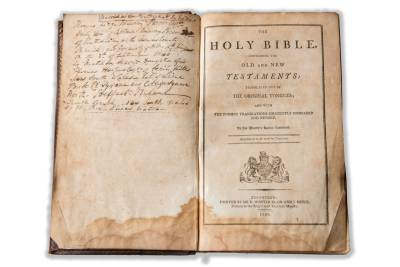

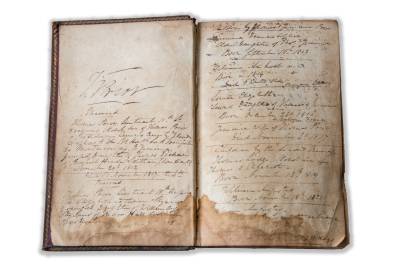

What little we know about Matilda is all positive. Her daughter Rosa recalled her as 'a wise woman and most tenderly sympathetic'.27) One piece of evidence tells us more about her: a book that belonged to her, with her name, address and a dedication as seen below ('Miss Matilda Harpur as a very slight expression of my estimation of her superior moral & intellectual qualifications & scientific attainments.'). The book was the Companion to the Bible. Intended for Bible Classes, Families, and Young Persons in General, published by the Religious Tract Society.28) It confirms that the Harpurs were Protestant with evangelical leanings, and that they lived in College Square, Belfast. It also provides evidence that Matilda Harpur was considered exceptionally bright.

Title page and dedication of the book presented to Matilda Harpur.

Title page and dedication of the book presented to Matilda Harpur.

The (teacher's?) initials may be 'A.F. Fr.' and it is dated Belfast 26 July 1839. The book is typical of its era in its presentation of science as evidence of God's creation. It is hardly light reading, especially for a 12-year-old! Its excellent condition may be because it was treasured - but equally probably, because it was little read.

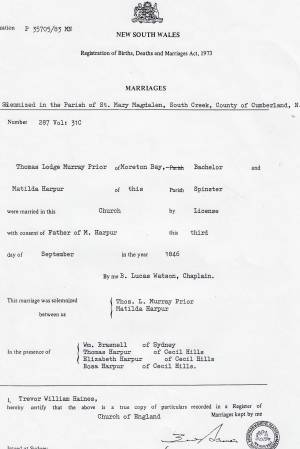

If Matilda had been a boy, what use would she have put her scientific and intellectual ability? As it was, the following year she migrated to Australia and 6 years later, on 3 September 1846, aged 18, married 26-year-old TLM-P at St. Mary Magdalene Church of England, South Creek, Cecil Hills.29)

30)

30)

It appears that Matilda and TLM-P had been writing to each other since the year after she arrived in the colony, that is, from the time she was 13 or 14 years old.31) While the letters allowed some familiarity, TLM-Ps efforts to establish himself in the north allowed little opportunity for visits. It also meant anxiety and long silences. Rosa Praed states that one of Matilda's letters took over five months to reach TLM-P, 'and then only through his chance meeting with the person who had bought in north, when Murray-Prior was delivering a mob of bullocks to the butcher in Brisbane.' There was reason for anxiety though one of Matilda's comments suggest that her fears were based on sensationalism rather than the more prosaic reality of Aboriginal people defending their land (but not being cannibals), or the ever-present danger of accidents and illness far from help. According to Rosa, Matilda wrote in her letter that, 'I am indeed thankful to know by the sight of your handwriting at last that you have not been murdered by bushrangers or eaten by Blacks.'32) Another time, again according to Rosa, TLM-P complained about her restraint (quite understandable if her father or step-mother read her letters, as was conventional at the time). Matilda asked 'Have I not given you the best proof of my affection and confidence in consenting to share your fortunes?'33) For a ardent young man angling for a declaration of passion, it was a dampening reply.

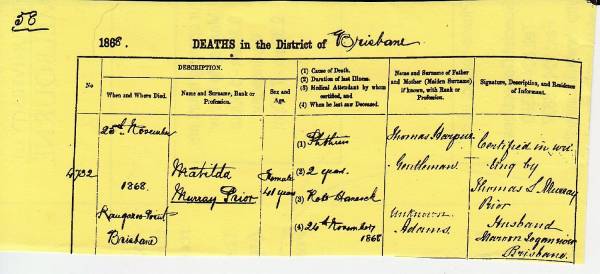

Much to the grief of her children, Matilda died of consumption (tuberculosis)34) when she was 41 years old at their home 'Montpelier' at Kangaroo Point, Brisbane on 25 November 1868 and was buried in Brisbane Cemetery. She was not alone in suffering from tuberculosis in this pre-vaccination era: in Queensland it was the 'largest single killer of working adults throughout the colonial period', though Pacific Islanders were particularly susceptible. As well, at the time Queensland had a higher death rate from the disease than England.35) Matilda's death certificate indicates that the diagnosis was made two years before she died, shortly after the birth of her last child, Egerton.36) Grief at her loss lingered. In 1882 her widower visited Lady Bowen, the wife of the first Governor of Queensland: she 'had tears in her eyes naming Matilda. She [Matilda] was so good, so kind she had never met a more unselfish woman'. Lady Bowen shook her head at the news TLM-P had remarried 'and still more when in reply I told her I had more children'.37)

Matilda's sisters Rosa and Elizabeth Harpur visited her after her marriage and they too married Queensland squatters, both in 1854. These relatives were especially important given the small (white) settler population - Queensland only had around 30,000 settlers in 1861, and about two-thirds were men.38) Rosa Harpur married Charles Robert Haly (1816-92) and lived on Taabinga Station in the Burnett district until he was forced to sell it due to 'diseases in his sheep and the rapid spread of speargrass'. In 1882 he became police magistrate at Dalby where, from 1891, he was also clerk of Petty Sessions. He died the following year, reportedly survived by 11 of his 14 children.39) In 1881, Nora M-P mentions a 'Rosie Haly', apparently named after her mother, as someone who might help Lizzie look after the children at Maroon while Nora had her baby in Brisbane. At least Nora expected it would be Rosie Haly 'in default of anyone more interesting'.40) In 1882 TLM-P visited Captain O. G. Haly when he saw the name on an office in the army's Intelligence office, where he was visiting one of his second wife's relatives. Captain Haly had been close to Charles Haly's brother William. The brothers had migrated together to Queensland, with Captain Haly commenting that 'all the sons of the family are in Australia' - except presumably himself.41).

Matilda's other sister, Elizabeth Harpur, married William Barker of Tamrookum station.42) They had six sons and two daughters.43) In the late 1860s, the well-known poet and novelist, James Brunton Stephens, was employed as their tutor at Tamrookum.

The three Harpur sisters and their families were close, and the small European population promoted everyday interactions.44) TLM-P had business dealings with his brother-in-law Charles Haly, as a note in TLM-P's 1864 diary refers to him paying interest, and that TLM-P offered to sell him some land.45) One son of Rosa and Charles, William O'Grady Haly, also illustrates the close connections.46) 'Mr O'Grady Haly' had been superintendent at Maroon to an earlier owner of that property.47); when he died, he named his (late) uncle TLM-P as a co-trustee/executor.48) Similarly, the small circles in which they moved is illustrated by the experience of Elizabeth and William Barker. When they retired from Tamrookum, they purchased 'Nunnington', a house at Kangaroo Point, Brisbane. It was sold to them by Frederick Orme Darvell, then Registrar-General of Queensland, and Nora M-P's uncle. Nunnington was named after the Darvall family home in Yorkshire.49)

Evidence of the literary bent of Matilda and her children survive in few copies of a hand-written family magazine that they produced at Maroon and called Maroon Magazine. The children's cousins, the Barkers, and James Brunton Stephens also contributed.50) Three issues are in Rosa Praed's papers in the Oxley Library. For more click on **Magazine**. In the early years at Maroon, the family's literary activities were likely to have been enhanced by the appointment of a new manager on 3 July 186551) of William Traill. He later become a well-known journalist.

European women living in what is now Queensland had a higher number of children than their sisters in the south, a phenomenon that was strongly supported by TLM-P and other politicians, 'spurred by fears of being engulfed, both numerically and culturally by foreign invaders'.52) Matilda was exemplary in this regard: she had 12 children during her 22 years of marriage. The personal cost was high: she was pregnant for nine of the years she was married - and perhaps for longer as we don't know if she had any miscarriages or stillbirths (stillbirths were not registered in the 19th century). It is also likely that her fecundity contributed to her early death aged 41. Each time she gave birth the possibility of death was real - in 1878, for example, a pregnant woman in Queensland had 'one chance in 21 of dying in childbirth'.53) In addition, Queensland's death rate was higher than other Australian colonies, that is, it was more dangerous and unhealthy for all its population.54)

Children's health and education

Matilda had her children when her husband was struggling to establish himself. They were not wealthy at this stage and, at least for her first six births, she endured the rough isolation that characterised the life of women settlers in rural Queensland at the time. Repeated childbearing - in this age when abstinence was the only effective contraception - undermined her health. When it was combined with tuberculosis, the result was tragic for all concerned. Matilda had 12 children during 1848-66. One way of looking at this is that she was pregnant for exactly half those 18 years, during which time she also raised eight and buried four of her children. The last stages of tuberculosis leaves little doubt that the sufferer is dying, so Matilda would have known she was leaving behind motherless children. When she eventually succumbed, her 8 surviving children ranged in age from 20 to 2 years old.

Patricia Clarke asserts that Matilda and her children avoided the worst of Brisbane's summer heat by spending some summers in Hobart. Subsequently, the younger boys, Morres, Hervey, Redmond, Hugh and Egerton 'became boarders at the private, highly regarded, non-sectarian High School in Hobart'.55) The older boys attended the school too. Thomas de M. M-P was at 'Mr. Shaw's school, Brisbane' then at 'the High School, Hobart, Tasmania'.56) Similarly, Hervey M-P was reported as 'a distinguished pupil at the Ipswich Grammar School, and subsequently at the High School, Tasmania, where he gained one or two important scholarships'.57) Table Talk 58) reports that Thomas de M. M-P attended the High School in Hobart in the early 1860s, when it was run by the Rev. R. D. Poulett Harris and was a 'notable' private school attracting boys from various regions of Australia. The school's eminence lasted until 1878; it closed in 1885.59) It is not to be confused with the later state-run Hobart High School which operated 1913-66 or its prestigious rival, the Hutchins School.

Even given the school's reputation, it was a long way to go for a cool summer retreat and difficult to understand sending young boys from Queensland to school there. One consideration was the strong belief at the time that Queensland's tropical climate sapped the vitality of young Britons, resulting in a degenerate 'race'.60) If so, the fear of degeneration was gendered: only the boys were sent to school while all the girls were taught at home by governesses, Matilda and older siblings.

Given the early death and alcoholism of some of Matilda's sons, to the modern mind a question that can't be avoided is: what kind of experience did the boys have at to school in Tasmania? Was it simply because, as their eldest brother thought when he wrote to his step-mother deploring the character of Hugh and Morres, that they were too young to be sent so far from home?61). If TLM-p's plans for Egerton are any guide, the boys were sent away to school when they were around 10 years old.62) This was the age of 'spare the rod and spoil the child', when severe physical punishment was routine in schools. Yet the High School's Headmaster, the Rev. Harris, 'was charged with assaulting boys with a cane in March 1860 and June 1868, the first case being dismissed and the second settled out of court'. How brutal would the caning need to be to warrant that action in the 1860s? Is it relevant that Harris was 'prone to depression', with a daughter who was committed to a mental hospital?63) Yet again, heavy drinking by all classes was a feature of Queensland life at the time, so perhaps no other explanation is needed than the boys reflecting the social conditions around them.64) Yet doubt remains: why did the younger boys have such difficult lives? Why did their loving step-mother later find them difficult, and their father note that it thought their behaviour 'all very hard, and cut me up.'65)

The M-P family papers includes this photo, identified on the back as Lyndhurst, New Town Road, Hobart Town, Tasmania.66) Lyndhurst was a popular name and nothing has yet been found about the homes in this photo, but does it hold a clue to why the children were sent to Hobart? Or, more probably, was it where Matilda and her children stayed when they went to Tasmania in November 1863- April 1864?67)

The M-P family papers includes this photo, identified on the back as Lyndhurst, New Town Road, Hobart Town, Tasmania.66) Lyndhurst was a popular name and nothing has yet been found about the homes in this photo, but does it hold a clue to why the children were sent to Hobart? Or, more probably, was it where Matilda and her children stayed when they went to Tasmania in November 1863- April 1864?67)

Matilda and TLMP's Children

The below photos, unless otherwise stated, are from Nora C. M-P's photo album. Other photos and some duplicates are, when stated, from TLM-P's album.68)

1. Thomas de Montmorenci (27 January 1848-11 December 1902).69)

Young 'Tommy' de Montmorenci M-P with his brother Morres, from his father's album.

Young 'Tommy' de Montmorenci M-P with his brother Morres, from his father's album.

Colin Roderick's biography of Rosa Praed refers to a letter by Matilda to her mother-in-law describing how their property Bromelton was isolated by a flood when she gave birth to Thomas: 'Having neither doctor nor nurse, and knowing that I might die before there was any hope of medical assistance, I endeavoured to prepare my mind for leaving this world.'70) Death was a distinct possibility for her baby too, given he was premature.71) It is not known if Matilda's difficulties were compounded by the knowledge that Emma Quin also gave birth in 1848 and that it would later be believed that the father was TLM-P.

For more on this Thomas M-P, go to Thomas de Montmorenci, Florence and Mary M-P

2. William Augustus* (18 August 1849-17 January 1850)72) had the same name as his late uncle. Like his elder brother, he was born at Bromleton; he was also buried there.73) Colin Roderick 74) describes how baby William had dysentery. Disastrously, the conventional medical routine at the time for someone with this form of diarrhoea including purging, that is, giving medicine designed to discharge whatever was causing the problem. That remedy increased any diarrhoea/vomiting and heightened dehydration. It is not surprising that so many babies with dysentery died, either from the original cause or because of the medical intervention by their desperate carers. In dying this way, 5-month-old William was one of many - but to his grieving family, it was a uniquely tragic event.

William's solitary grave in Bromelton's garden.75)

William's solitary grave in Bromelton's garden.75)

3. Rosa Caroline (27 March 185176)- 2 April 1935). She was born at Bromelton station and, like her elder brother, baptised by the Rev. Benjamin Glennie.77) Her family called her 'Rosie'. Like her sister Lizzie, she had a deeply loving relationship with her ailing mother.

Rosa made what seemed the ideal marriage for an Anglophile colonial writer when she married Arthur Campbell Bulkley Mackworth Praed on 29 October 1872. As she latter wrote, her family and friends 'all wanted to be English', and Praed seemed a particularly dashing member of the English gentry, with a lifestyle bankrolled by his father's interests in a bank and brewery in London. Campbell Praed c. 1867, photo at State Library of Queensland:

Perhaps the clinching detail to the aspiring writer was that his uncle was a well-known poet Winthrop_Mackworth_Praed. Other current and future members of the family were also artistic - for example, there is a well-executed portrait of Rosa in the SLNSW attributed to an Emily Praed.78). To the young Rosa, her suitor embodied cultured English gentry. Sadly, neither of the couple lived up to the other's ideal. Divorce in these times was very difficult, expensive and entailed social disgrace, so the unhappy couple produced children but separated in 1899. Today it is probable that Rosa would identify as a lesbian; as it was, she wrote to her friend and co-author Justin McCarthy that (by implication, heterosexual) sex was 'a side of life that has always repelled me.'79) It did not help that Campbell Praed had a reputation for unfaithfulness. The heroine who was reared in the Victorian ideal of female innocent/ignorance, and then married someone unsuitable, became a common theme in Rosa's books. That theme resonated with many women's experiences, especially given that divorce was very difficult, expensive, condemned by churches, and meant social disgrace.

The marriage did not start well. Their first home was the romantically named 'Monte Christo', a 500 square mile property on Port Curtis Island near Gladstone. The property was a joint venture by Campbell Praed and a former vetinarary surgeon, Dr Samuel Joseph Wills.80) Rosa's romantic dreams were dashed by the reality of scrubby land and hordes of mosquitoes.81) Four years later, they left the island with Praed's hopes of making a colonial fortune ended.82)

The Praeds left Australia in 1876 to live in England, but again reality was no match for Rosa's colonial fantasies. Praed's family circle tended to more insular gentry/business people rather than cultured sophisticates. Despite personal tragedy, Rosa forged her own way in England, becoming a prolific novelist. She wrote over 50 novels, many of them with controversial social themes. The height of her fame was the 1880s and 1890s. Almost half her novels had Australian settings or characters, and she only visited Australia rarely.83) Instead, she relied on her family, initially mostly her step-mother and father, to refresh her mind regarding Australian details. After her father's death and her step-mother's removal to live in England, Rosa gained much of her Australian details from her sister Lizzie Jardine and other siblings.84) In particular, she directly incorporated the experiences of her brothers Morres and Hugh into her stories.85) In keeping with her father's ideals, she supported Irish home rule, largely through collaboration with fellow writer and Irish nationalist Justin McCarthy.86)

For more, click on Rosa Praed.

4. Morres(1587) May 1853 - 2988) October 1897)89) Morres was born and baptised at Bromelton Station90); he never married. In April 1880, TLM-P registered a mortgage on Morres' property at Cleveland, Brisbane. 91) In the late 1880s/early 1890s, like his brother Hugh, Morres was living on Aberfoyle Station, jointly owned by his father and his brother-in-law, John Jardine.92)

Morres died, lonely and depressed, when he was 44 years old. As Janet McCalman outlines, it was not an unusual fate for people in an emigrant society.93) When he died, Morres had been living for at least two years at Bulliwallah Station in the Clermont District, some 920 km northwest of Brisbane. He wrote a sadly revealing letter to his step-sister Dorothy a month before he died. For more click on Letter.

His step-brother Robert M-P states that Morres died from kidney failure. This is not incompatible with Isobel Hannah's claim that he died 'from the scourge of the “Out-back,” berri berri'.94) She presumably meant beriberi, a severe and chronic form of thiamine (B1) deficiency caused by, among other things, dehydration. One of the problems of all migrants was adjusting to new conditions, and an entry in TLM-P's diary when Morres was 10 years old gives an indication how difficult it was to adjust to a semi-tropical climate: 'Morres had a sort of sun stroke and was very bad at first but recovering … poor little fellow'.95) If Morres had a weakness in his kidney function, then the heat and lack of water in summer in outback Queensland was a lethal combination.

There are numerous photos of Morres in Nora and TLM-P's albums: the one below is from TLM-P's. See above for a photo of him with his eldest brother Tom.  For more photos of Morres and his grave, click on Morres

For more photos of Morres and his grave, click on Morres

5. Elizabeth (Lizzie) Catherine (29 October 185496) - 19 December 1940). She was baptised in Brisbane on Ash Wednesday 1855.97)

This photo is of Lizzie in fancy dress.98)

This photo is of Lizzie in fancy dress.98)

At some stage before 1882, Lizzie visited her sister Rosa in England. TLM-P arranged the trip to discourage her relationship with John (Jack) Robert Jardine.99) His misgivings about the character and lack of financial acumen of Lizzie's chosen mate was shared by her step-mother Nora. Despite her father's misgivings, and Lizzie's frail health,100) she married Jack Jardine at Maroon Station on 14 June 1883.101) What could be accepted in a father, was not forgiven in a step-mother. Three years into her marriage, Lizzie wrote to Rosa: 'When I married Jack I knew that for years to come I should have plenty to contend against. But there is much to sweeten toil. Someday I look forward to a more civilised home. Meantime we are content and live for each other … [I think Nora] only pretends to like Jack for my sake and [I] cannot forget the hard things she said about him … He is only an Australian bushman, but he is true, loyal and the tenderest of husbands and we love each other. When I say that I say everything.'102)

Jack Jardine was part of a North Queensland family whose English gentry antecedents impressed TLM-P.103) Jack's father (His first name was also John) was famed for pioneering feats and for founding the settlement of Somerset at Cape York104) The name Jardine was also well-known due to the transgressive marriage in 1873 of Jack Jardine's eldest brother Frank to Sana Solia nee De Boos, a niece of the king of Samoa.105)

Jack Jardine had taken charge of Vallack Point Station, near Somerset (Cape York), in 1868 when he was only 21 years old. At some time he appears to have been in the Barcoo area in Central West Queensland, as Nora wrote to Rosa reassuring her that, if Lizzie did live there, it was no longer 'the unattainable uninhabitable 'terra incognita' … You can't stretch a line 80 miles in a given direction there now without touching a piano or a sewing machine - Ladies and babies are as thick as bandicoots … and the former are very angry if you hint there may possibly be a more desirable place of residence.'106) Despite this reassuring description of the Barcoo, after their marriage, Lizzie stayed with the Jardines in Rockhampton while her husband set up a home for her at Aberfoyle Station in western Queensland (just over 1,000 km northwest of Brisbane), breeding sheep and cattle. TLM-P bought the property in partnership with Jack Jardine in 1885 to try to secure Lizzie's future.107)

As with so many of TLM-P's ventures - not to mention Jack Jardine's - the property was not profitable, with the 1890s drought the last straw.108) A key reason was its unreliable water supply.109) TLM-P's 1892 will states that the property cost him £10,070 and that, by then, the partnership had a £8,000 mortgage.110) Aberfoyle was sold after TLM-P's death and, in 1905, the Queensland Supreme Court was told that the loss that entailed was the chief reason the estate could not afford to pay the bequests.111) It also appears that Lizzie's youngest brother Egerton also lived on the property112) [to do: loose 1888 balance sheet for Aberfoyle station in ML - was in reported of Queensland post service for 1864, donated with diaries, 4pp.] When Jack Jardine died from pneumonia113) at Southport in 1911, he worked for Messrs Aplin, Brown and Co., a major mercantile company operating in north Queensland.114) For more, click on the Jardines.

6. Hervey Morres (9 September 1856115)-1 January 1887.116) His godmother was his English step-aunt Jemima Prior.117)  Photo: Hervey as young man, full of promise.118)

Photo: Hervey as young man, full of promise.118)

Hervey was born at Hawkwood Station, baptised by the Rev. Mr Dodd, and was buried in South Brisbane (later called Toowong) Cemetery.119) After school in Tasmania, Hervey gained a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Sydney, where he lived at St Paul's College.120) Despite his alcoholism, he became a barrister and Master of Titles for Queensland. He was also a member of the 'Colony of Queensland Society'.121) From the early 1880s until 1885, Hervey leased one of Brisbane's historic houses, Middenbury which now has the address of 600 Coronation Drive, Toowong.122)

Hervey married Margaret (Maggie) McDonald in 1881. It was a short-lived and troubled marriage, with Hervey dying aged 30 when his son, Hervey McDonald M-P, was four (born 25 April 1883).123) Baby Hervey's parents followed family tradition and had him baptised at All Saints Church of England, Brisbane.124) Even before Hervey's death, TLM-P and Nora assumed responsibility for Maggie and her son. In August 1882, when TLM-P was away, they came to stay at Maroon.125) Maggie and her son also accompanied TLM-P, Nora and other family members on their visit to England in 1885.126)

The following report of Hervey's death highlighted his potential: that 'at Sydney University … he … graduated B.A. with great credit, being nearly at the head of the list in his year. Shortly afterwards he was called to the Queensland Bar, and in March, 1883, was appointed Crown Prosecutor for the Southern district. In July, 1884, he was appointed Master of Titles, which office he held up to his death. He bore a good reputation as a barrister, and his knowledge and grasp of the laws relating to real property are said to have been very considerable.'127)

For more on Hervey and Margaret M-P, click on Hervey

7.Redmond (6 October 1858128) - 21 January 1911129) 'Reddie', as his family called him, was born at Kangaroo Point, Brisbane and baptised there by the Rev. B.E. Shaw.130) Redmond was a family name; TLM-P visited the house at Brighton where an earlier Redmond M-P had lived.131) In 1882, the 24 year old Redman was being 'obstinate', causing problems for his step-mother while his father was away.132)

He died aged 52 shortly after boarding a train to go to Bowen for medical treatment after complaining of being unwell. He was described as having lived in Proserpine, north Queensland for over 20 years. He had pursued mining interests (the area is known for its gold) in the district and had, shortly before his death, acquired an interest in a farm at nearby Kelsey Creek.133) To date we have no more information about the adult Reddie, other than a comment by his step-mother in 1880 that Alice Bundock was attached to him (Alice's sister Mary became the second wife of Redmond's eldest brother Thomas de M. M-P).134) The attachment did not come to anything as Redmond apparently died unmarried. We know nothing about any other attachments, or the reason for the family's relative silence about him.

The photo, from TLM-P's album, is of Reddie (right) and his brother Hugh.  For more photos, click on Reddie.

For more photos, click on Reddie.

8. Weeta Sophia* (24 June 1860135)- 27 July 1860.136) She was born at Cleveland, dying there just over a month later. She was buried at Cleveland, but not baptised.137) Her name is engraved on the marble on the front of the family grave at Toowong cemetery.

9. Hugh (26 July 1861138) - 28 December 1896).139) If later belief is correct, Hugh's half-sister was born less than a fortnight after Hugh, to TLM-P and Annie Smith.

The photo is of Hugh (right) with his older brother Redmond.140) Hugh was born at Cleveland and baptised at Brisbane by the Rev. John Bliss.141) In 1882, his step-mother wrote to TLM-P that 21-year Hugh was 'breaking out again', probably referring to his drinking. TLM-P immediately wrote to him, hoping 'it will have some effect upon him.'142)

The photo is of Hugh (right) with his older brother Redmond.140) Hugh was born at Cleveland and baptised at Brisbane by the Rev. John Bliss.141) In 1882, his step-mother wrote to TLM-P that 21-year Hugh was 'breaking out again', probably referring to his drinking. TLM-P immediately wrote to him, hoping 'it will have some effect upon him.'142)

By the late 1880s or early 1890s Hugh, like his brother Morres, was living on Aberfoyle Station, jointly owned by his father and his brother-in-law, John Jardine.143) Isobel Hannah wrote that he died 'from sunstroke on a lonely track between Annie Vale and Doongmabulla', in central Queensland.144) He never married.

For more photos, click on Hugh.

10. Lodge (August 1863145) - September 1863).146) He was born and baptised at Brisbane, dying when one month old; he was buried in the family plot at Toowong (then known as the South Brisbane) Cemetery.147) Not surprisingly, after he died Matilda wanted a holiday. A month later TLM-P decided to vacate their Brisbane house so it could be let out while Matilda and the children went to Tasmania for six months.148) The break may have helped Matilda recover but appears to have proved too much for TLM-P's fidelity: Clara van Zuethem gave birth to a son on 25 January 1864 whose father was believed to be TLM-P.

11. Matilda (26149) January 1865 - 11 May 1865.150) She was christened in Brisbane but, when three and a half months old, joined her brother Lodge in the family plot at Toowong (then known as the South Brisbane) Cemetery.151)

12. Egerton (5 October 1866152)- 1 September 1936). Egerton was born at Maroon153) and was two-years-old when his mother died. 'Egerton' appears to be a family name through TLM-P's mother. Significantly for TLM-P, it had aristocratic connections as the family name of the Dukes of Bridgewater and Sutherland, as well as of various earls. In 1882, TLM-P stayed with John Skynner Egerton Bishop who lived at Brighton.154) For more, click on Bishop.

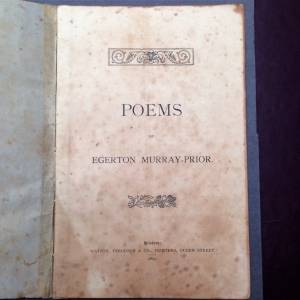

Egerton inherited his grandfather's (and mother's?) love of poetry, publishing his Poems (Brisbane: Watson, Ferguson & Co. Printers) in 1893.155)

Cover of Egerton's poems, ML A821/P658.2/1A1. For more, click on Egerton's poetry.

Cover of Egerton's poems, ML A821/P658.2/1A1. For more, click on Egerton's poetry.

Egerton and Sara Arbuthnot Crawford (b. St James' Park, London) married on 30 April 1894 at St Andrew's Church of England, Lutwyche in Brisbane.156) They lived at Moorlands, Malvern Hills, Blackall in south-west Queensland157) and had one son, Egerton Thomas Crawford M-P, who was born in Brisbane who died less than a month old. For more, click on Baby Egerton. Egerton and Sara had no other children and Sara died in c.1903.158) He became a diary farmer at Nambour in Queensland, but became bankrupt.159) In a codicil to his will just before he died in December 1892, TLM-P provided for Egerton's £3,000 legacy being paid to him before his father's death; presumably to protect the money from creditors, he also stipulated that no income be paid to Egerton (or his younger brothers) while bankrupt, although it could be paid to any wife or children.160)

In 1905, Egerton re-married, to Annie Grace (known as Grace) Crawford.161) Was she a relative of Sara's, perhaps a sister? The original certificates are needed to help clear up this mystery.162)

Egerton is buried in the family plot at Toowong Cemetery, Brisbane.

Photos of Egerton:

163).

163).

Later generations believed that, around five months after Egerton's birth, another baby was born to TLM-P, this time with Mary Ingoldsby.

Who?

This photo is probably one of Matilda's sons when adult, but which one?  164)

164)

Evidence

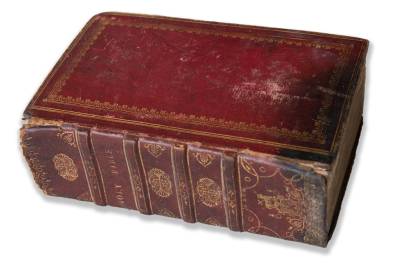

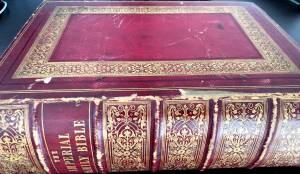

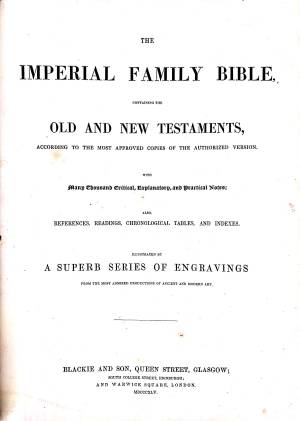

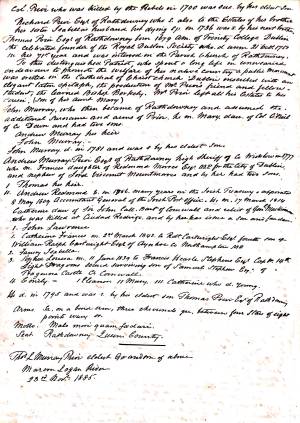

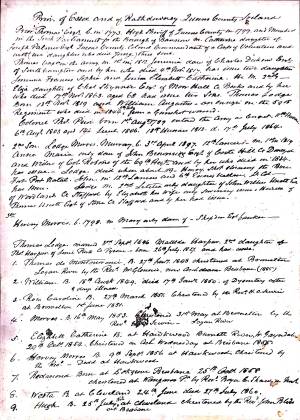

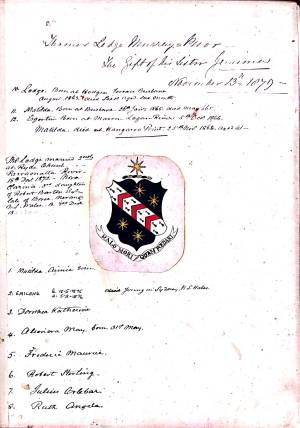

One source of information are the family bibles with names and dates of family members written it them, as shown by the next 3 photos of one family bible.

165)

165)

The next pages are from the Family Bible, as shown in the first photo, given to TLM-P by his half-sister Jemima166):

Key Genealogical Sources: Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Colonial Gentry, Melbourne: E.A. Petherick, 1891-95, pp.49-50; TLM-P, ‘Questions to be answered by T.L.M-P’, 6pp Memoranda by the Herald Office, Somerset House, London re Burke’s Colonial Gentry; [Thomas M-P], [Thomas A. M-P], Murray-Prior Family, booklet, October 2014; Thomas Bertram M-P, Some Australasian Families Descended from Royalty, ms, n.d, pp.7-14, NLA; TLM-P, genealogical notes in John & John B. Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland: M to Z, London: Henry Colburn Publisher, 1846; Robert M-P, The Blood Royal of the Murray-Priors, ms written 1901-05 NLA Nq929.2M984.

N.B. The above references give contradictory information regarding names and key dates, hence the references to births, deaths and marriage registrations. See https://www.bdm.qld.gov.au/IndexSearch/querySubmit.m?ReportName=BirthSearch, noting that certificates need to be bought to find out more than year and parents names.