TLM-P's Career in Politics and the Post Office

TLM-P was active in community affairs before Queensland existed as a separate colony. By 1851 he was a Justice of the Peace (JP) and a committee member of the Moreton Bay and Northern Districts Separation Association, which worked to create what is now known as Queensland as a separate colony.1) Just before Queensland was proclaimed a separate colony, he was among the 19 eminent men who founded the Queensland Club. He went on to become Vice-President in 1889-90.2) It is understood that his son Thomas and grandson Thomas were also members along with another son Hugh.3) At the time, the Queensland Club was the only meeting place for prominent men, notably squatters like TLM-P.4) The squatters were never a unified bloc and not always anti-liberal.5) However, TLM-P was identified with 'the conservative rural interest' as opposed to 'the urban-liberal interest'.6) Both groups were determined to consolidate their interests.

When Queensland separated from the colony of NSW in 1859, its settler (white) population was only around 28,000.7). The political system strongly favoured rural interests, so TLM-P largely represented dominant interests. The idea of mass democracy was still a radical idea and property owners were generally firm in their conviction that they alone had the right to rule - even if it did mean a few women managed to vote before legislation was amended to exclude them. TLM-P stood for the seat of East Moreton in the first election in 1860, urging electors to protect 'the interests of the squatter, the first occupier of the land'.8). When he failed to be elected, his sights turned to the public service.9)

In mid-1861 the Queensland Parliament decided that the position of Postmaster-General should be combined with that of Postal Inspector and no longer be held by a government minister.10) The following year, TLM-P was appointed the new Postmaster-General. Darbyshire states that Matilda M-P's brothers-in-law, fellow squatters William Barker and Charles Robert Haly, provide part of the necessary bond.11) As TLM-P was offered the position when he was 'in utter ignorance' about running a postal service, he first took leave to go to Sydney where he was instructed in his new duties by the NSW Postmaster-General Major [William] Christie12) and Secretary of the Department, Thomas Abbott. On his return he appointed Postal Inspector (on 6 November 1861) and then also to the position of Postmaster-General on 1 January 1862.13)

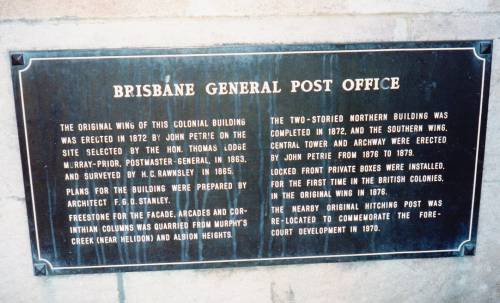

Documents from his time were once located at the Brisbane General Post Office Museum: this museum was closed in 2005 and the documents' whereabouts are not known.14)

TLM-P's periods as Postmaster-General are as follows:

1. 1862 - 1 March 1866: After TLM-P served as Postmaster-General for four years, Parliament decided that the position should again be held by a politician. In order to be eligible, TLM-P was nominated for life to Queensland's upper house (members of whom were then appointed by the Governor), the Legislative Council on 22 February 1866, remaining a member until his death in 31 December 1892. Members of the Legislative Council were not elected, but nominated and dominated by conservative squatting interests.15)

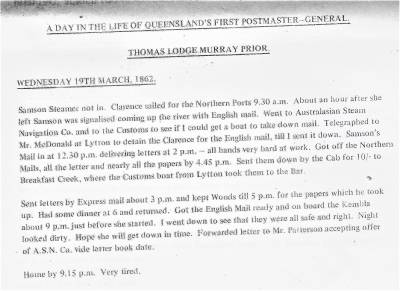

The following is a transcript of one page of his diary from this period. 16)

This collage is entitled 'First Queensland ministry' with TLM-P's photo in the top left corner, so perhaps refers to the first ministry he served as Post-Master-General.17)

2. 21 July - 7 August 1866: TLM-P served as Postmaster-General in the government led by Sir Robert Herbert. That Government fell in July, meaning that TLM-P again lost his position as Postmaster-General, though he stayed on for another month until a successor was found.18)

3. 15 August 1867 to 25 November 1868: TLM-P again served as Postmaster-General under the government of the conservative Sir Robert Mackenzie. When a more liberal government was elected, TLM-P was out of office.

This period was one of more fluid party allegiances, and in 1867-68, TLM-P sided with church and women's groups in opposing a Contagious Diseases Act. Its passing meant that any woman in Queensland suspected of being a prostitute could be compulsory detained and medically examined.19)

4. 3 May 1870 to 8 November 1874: TLM-P was again Postmaster-General when the government reverted to the more conservative ministry headed by Sir Arthur Palmer.

It would take a specialised historian to properly access TLM-P's success as Postmaster-General. We do know that during 1862-74, when TLM-P was predominantly the Postmaster-General, the service expanded both in the type of service offered, e.g. from 1865, saving bank deposits could be make at Queensland post offices, and its reach. Staff also increased: in 1865, TLM-P had a postal staff of 28; by 1872 the staff totalled 50.20) TLM-P was responsible for the much-needed new General Post Office21) which opened in Brisbane in 1872. Another indication is the growth in post offices, from 23 in 1862 to 139 ten years later.22) In the next decade, travelling post offices were opened on trains, the post and telegraph departments were amalgamated, and telegraphic communication was extended to remote areas, such as Cape York and the Gulf country.23) Much of the expansion was the result of the rapid growth of the white population - in 1861 to 1864 alone, Queensland's population (largely excluding Aboriginal people) doubled from just over 6,000 to just over 12,500. [check hist stats] How much TLM-P facilitated the subsequent expansion of postal services to meet the increasing demand is not known. However, as a representative of the squatters' faction, it was in his own strong interest to maintain efficient and widespread postal services. And he certainly was active: his 1863 diary indicates that he rode 1,017 miles (1636km) as well as travelling by coastal steamer in less than two months in a tour of inspection of the postal service.

An admiring view of his achievements as Postmaster-General comes from his entry in Australia's Representative Men. It states he 'may be said to be the first to have initiated the through mail service' (presumably to the UK), and the confidence of the authorities in his abilities was seen in his selection to negotiate with Batavia (now Jakarta) regarding the postal service (though he was unable to travel there himself). It summed TLM-P up as a 'safe representative of the people' due to his 'unserving integrity and disinterested loyalty'.24)

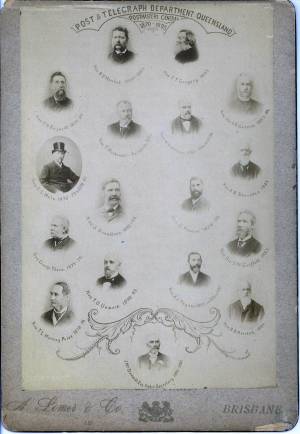

TLM-P (bottom left) with subsequent Postmasters-General of Queensland.25)

TLM-P has written on the back that this photo is of the 'Telegraph Department, officials Chief Office[ers?] Brisbane 1870 [? the last digit is unclear].26)

TLM-P has written on the back that this photo is of the 'Telegraph Department, officials Chief Office[ers?] Brisbane 1870 [? the last digit is unclear].26)

Following Tom A. M-P's initiative, this plaque on the Brisbane GPO has recently been restored.

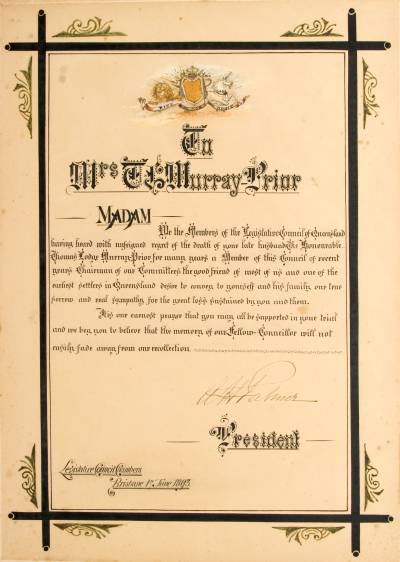

By 31 July 1889, TLM-P had impressed his peers sufficiently to be appointed Chairman of Committees in the Legislative Council, a post he retained until his death. The elegant illustrated letter of condolence stressed his friendship with 'most' of his political colleagues, and his status as a Queensland pioneer.27)

Throughout his political career, TLM-P was active in defence of broad rural as well squatter interests: amongst other things he took charge of getting the Crown Lands Alienation Act of 186828) through the Legislative Council - ironically this act aimed to stop people selecting land in their relatives' names, something it is likely TLM-P did himself. He also consistently opposed the payment of members of parliament, effectively limiting parliamentarians to those who could afford to work voluntarily.29)

Reference: D. Waterson, A Biographical Register of the Queensland Parliament 1860-1929, Canberra: ANU Press, 1972, p.135.

Elise Barney

TLM-P had a very public clash with one of the few higher status women to have a lucrative, responsible employment. For TLM-P, conservative views on women's roles and self-interest combined when he was offered the position of Postmaster-General, over the claims of Elise Barney, Brisbane Postmistress during 1855-65.30) Historian Desley Deacon has outlined how Elise Barney had taken over the lucrative position when her husband, the previous postmaster, died. Her son Whiston Barney became her assistant. When Queensland became a separate colony, Elise Barney automatically became the head of the new postal department, responsible only to the politician appointed Acting Postmaster-General. Her work was soon officially found to be 'in every respect satisfactory'. When the new Queensland Government decided to combine the Postmaster-General position with that of Postal Inspector and to make it a public service position, a 'long and bitter struggle' ensued between TLM-P and Elise Barney, supported by her son. It was not helped by TLM-P having to have his office in the building in which the Barneys had lived and worked for years. As well, combining the Postmaster-General position with that of Postal Inspector travelling throughout the colony, suggests a deliberative move to exclude Mrs Barney31). Whiston Barney resigned under pressure in mid-1883; in 1864 Mrs Barney was placed on leave after a clerk 'nominally' under her supervision embezzled funds. A Public Service Enquiry criticised both TLM-P and Elise Barney; a subsequent parliamentary Select Committee exonerated them. It appears that sympathy and blame remained equally proportioned between the two. Elise Barney was retired on a generous pension while TLM-P, as seen, was appointed to the Legislative Council when the Postmaster-General position again became a ministerial one.32)