Table of Contents

Boys' and girls' education

The girls

Typically of the nineteenth century, the girls were educated at home. We know that the elder siblings and mother/stepmother acted as teachers as well as an unknown number of governesses and other specialist teaches at different times. In March 1866 Miss Medley was paid £4.6.8 'for tuition'. It is possible that one of Matilda's family also taught them as there is an entry in November 1867 of Tom de M. M-P paying R. Harpur £4 'salary'.1)

Music was seen as an essential part of a young lady's education, and later in the month, Mr Atkinson was paid £2.16.0 for 'Music lessons for Rosa and 3 pieces music'. In February 1867, Paul Atkinson was paid £4.4.0 for 'Rosa's music'. In January 1868, noted Brisbane musician Madame Mallalieu, later Henrietta Willmore was paid £2 for 'Rosie's music lesson'. Virtually all upper middle class homes had a piano; the one at Maroon was tuned in October 1866 and November 1867 by Mr John Crump for £2.2.0. There were further payments to him listed as 'salary', e.g. November 1867. In 1867 at least, the family also had a subscription to the Philharmonica Society2)

The boys

Brisbane

In contrast, boys were sent away to school when still young. In 1862, Thomas de M. M-P and Morres attended 'Mr. Shaw's school, Brisbane' known as the Collegiate School - a Church of England school whose headmaster was the Rev. Bowyer E. Shaw. It was designed for 'sons of the gentry' and charged accordingly: £80 per year for boarders. Perhaps for that reason, it did not last long.3) We only know the two boys were there in 1862 because of a report in the newspaper that Tom won the prize for English and Morres the fourth class prize for Latin.4) In his 1888 diary, TLM-P visits a chemist in Newcastle only to discover he was not a son of 'my old friend Boyer Shaw'.5)

There was no comparable school in Brisbane until 1868 when Brisbane_Grammar_School opened.

Ipswich

Ipswich_Grammar_School opened on 7 October 1863. The founding headmaster until late 1868 was Stuart Hawthorne who had been deeply influenced by Prof. John Woolley's progressive ideas for education at the University of Sydney.6) Hervey M-P was reported as having initially attended Ipswich Grammar School where he was 'a distinguished pupil'.7) While at Ipswich Grammar, in 1872, Hervey was awarded The Tiffin Scholarship worth £20 and his brother Hugh the Thorn Scholarship worth £12.8) Hervey later attended the High School, Tasmania, 'where he gained one or two important scholarships'.9)

Hobart

Perhaps because Mr Shaw's school closed, Matilda's sons all attended the High School in Hobart in the early 1860s.10) Patricia Clarke asserts that Matilda and her children avoided the worst of Brisbane's summer heat by spending some summers in Hobart. As a result, Morres, Hervey, Redmond, Hugh and Egerton, 'became boarders at the private, highly regarded, non-sectarian High School in Hobart'.11). In 1901 Rosa recalled that, as a girl of 12 and 16, she visited Hobart, i.e. in 1863 and 1867.12) It is not to be confused with the later state-run Hobart High School which operated 1913-66, nor with its prestigious rival, the Hutchins School.

![Domain House - previously the High School, Hobart [[http:///ontheconvicttrail.blogspot.com/2013/03/domain-house-high-school-of-hobart-town.html|Domain House - previously the High School, Hobart]] Domain House - previously the High School, Hobart [[http:///ontheconvicttrail.blogspot.com/2013/03/domain-house-high-school-of-hobart-town.html|Domain House - previously the High School, Hobart]]](/mpwiki/lib/exe/fetch.php?w=300&tok=3e9154&media=domain_house_3.jpg) Domain House - previously the High School, Hobart, from ontheconvicttrail.blogspot.com.

Domain House - previously the High School, Hobart, from ontheconvicttrail.blogspot.com.

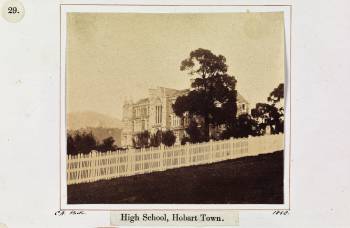

The High School in 1858, courtesy Libraries Tasmania. Both photos with thanks to Margaret Dalkin.

The High School in 1858, courtesy Libraries Tasmania. Both photos with thanks to Margaret Dalkin.

Rev Richard Deodatus Poulett-Harris, headmaster 1857-85, in Masonic costume. He was the first Grand Master of Tasmanian Masons. source: Tasmanian State Library and Archive Service (Janine Tan, Librarian) with thanks to Margaret Dalkin.

Rev Richard Deodatus Poulett-Harris, headmaster 1857-85, in Masonic costume. He was the first Grand Master of Tasmanian Masons. source: Tasmanian State Library and Archive Service (Janine Tan, Librarian) with thanks to Margaret Dalkin.

State Library and Archive Service | Libraries Tasmania

Even given the school's reputation, it was a long way to go for a cool summer retreat and difficult to understand sending young boys from Queensland to school there. One possibility is that Matilda had relatives in Tasmania. No obvious connections have been found but there are a number of Harpurs listed in the Tasmainian Names Index (thanks to Margaret Dalkin). One consideration was the strong belief at the time that Queensland's tropical climate sapped the vitality of young Britons, resulting in a degenerate 'race'.13) Certainly when the school advertised in Queensland, it emphasised its healthy location.14) Yet there were limits to the fear of degeneration: only the boys were sent to school while all the girls were taught at home by governesses, Matilda, Nora and older siblings. And why not send the boys to a prestigious school in Sydney, for example, The King's School?

When we consider the early death and alcoholism of some of Matilda's sons, to the modern mind a question that can't be avoided is: what kind of experience did the boys have at school in Tasmania, so far away from family? Was it simply because, as their eldest brother thought when he wrote to his step-mother deploring the character of his brothers Hugh and Morres, that they had been too young to be sent so far from home?15) If TLM-p's plans for Egerton are any guide, the boys were sent away to school when they were around 10 years old. This is confirmed by Hugh, then 11 years old, being at school in Hobart when his father and Nora married.16) Matilda's illness and death, however, may have meant that the boys were sent there at a younger age.17)

This was the age of 'spare the rod and spoil the child', when severe physical punishment was routine in schools. Yet the High School's Headmaster, the Rev. Poulett Harris, 'was charged with assaulting boys with a cane in March 1860 and June 1868, the first case being dismissed and the second settled out of court'. In the first case, the boy apparently was returned to school by his father; in the second the issue appeared to be that the boy was no longer a pupil there, and had grabbed the cane from Harris when the later tried to cane him. Were these incidents a reflection of a too-ready recourse to the cane, even for this time? Is it relevant that Harris was 'prone to depression', with a daughter who was committed to a mental hospital? What was the impact on him when his 5-year old son burned to death in a bonfire accident in 1860?18) Whatever was the case, TLM-P was satisfied, as he allowed himself to be named as a referee when the School advertised for Queensland pupils.19) In January 1877 it was reported that three Queensland boys were at the school, including 'young Prior', only identified as TLM-P's son, winning a special prize for proficiency in French. It is not known if the two other 'Queensland boys' were his brothers.20)

We need to be cautious assuming childhood difficulties resulted in adult problems. Heavy drinking by all classes was a feature of Queensland colonial life, so perhaps no other explanation is needed than the boys reflecting the social conditions around them.21) Additionally, former pupils admired Poulett-Harris enough to erect this memorial to him, now in the Queens Domain Hobart. Yet doubt remains: why did the younger boys have such difficult lives? Why did their loving step-mother later find them so very difficult, and their father write about their behaviour, that it was 'all very hard, and cut me up.'22)

Yet doubt remains: why did the younger boys have such difficult lives? Why did their loving step-mother later find them so very difficult, and their father write about their behaviour, that it was 'all very hard, and cut me up.'22)

The M-P family papers includes this photo, identified on the back as Lyndhurst, New Town Road, Hobart Town, Tasmania.23) Lyndhurst was a popular name and nothing has yet been found about the homes in this photo, but does it hold a clue to why the children were sent to Hobart? Or was it where Matilda and her children stayed when they went to Tasmania in November 1863- April 1864?24) or where Matilda stayed when she returned to Hobart in February 1868, accompanying by a daughter and two sons as well as Maroon employee Mr Pearse and his wife.25)

The M-P family papers includes this photo, identified on the back as Lyndhurst, New Town Road, Hobart Town, Tasmania.23) Lyndhurst was a popular name and nothing has yet been found about the homes in this photo, but does it hold a clue to why the children were sent to Hobart? Or was it where Matilda and her children stayed when they went to Tasmania in November 1863- April 1864?24) or where Matilda stayed when she returned to Hobart in February 1868, accompanying by a daughter and two sons as well as Maroon employee Mr Pearse and his wife.25)

A further clue regarding the boys' education is the list of TLM-P's cheques. In March 1866 one cheque was to 'Townson Esq' for £8 for 'Boys tuition'. The same list indicates that simply getting one boy to Tasmania was expensive even before paying the school fees. One cheque is for £2.10 to pay 13 year old Morres' passage to Sydney and a further £8 'for Morres' expenses to Tasmania'. In November 1866, TLM-P wrote a cheque to Rev. R.D. Harris for £17.9.6 for Morres' tuition. A note of a cheque in March 1867 £30 indicates that it was for a quarter, making the annual school fee £120. In addition, an additional £10.8.0 was 'residue to pay Morres' passage etc' with 8/- of this amount the commission to send money orders. It was not cheap to travel to Tasmania. In January 1868, three cheques were made out to Matilda regarding such expenses: £1 for expenses; £32 expenses for Hobarton; and £15 'passage … Sydney' (steamship fares) to Hobart for Matilda, Rosie, Morres and Harvey'.26)