Table of Contents

Matilda Murray-Prior nee Harpur

Matilda (1827-68) was TLM-P's first wife and the second daughter of Thomas Harpur of Cecil Hills near Liverpool (now western Sydney).

The only known photo of Matilda.1)

The only known photo of Matilda.1)

Matilda's family came from a Northern Ireland. She was born 'in the parish of Desertcreat, near Tullyhogue, south of Cookstown, a Protestant plantation town in the northern Irish county of Tyrone.' Her mother, Rose or Rosa (nee Adams) died in 1835 when she was 32 years old.2) In after years, little was known about her: TLM-P stated 'unknown', when required to give her Christian name on his wife's death certificate (see below).3) Another son-in-law gave her name as Rose though Patricia Clarke thought it was Rosa.4) After the death of Matilda's mother, Patricia Clarke states that the family moved to Dublin. There Matilda's father married Mary Jane Speer, whose father was a Dublin solicitor.5) Before they emigrated, Matilda and her family gave their address as Lime Park, County Tyrone (the place she also gave as her birthplace on her son Redmond's birth certificate) and College-square North, Belfast.To emigrate, they travelled to the English port of Plymouth and, on 24 June 1840, left aboard the newly built barque the Lord Western under Captain Lock.6) The journey took over three months, with them arriving in Sydney on 5 October 1840, a year after Matilda's future husband.

The Lord Western's passenger list7) reveals that the Harpurs sailed with 233 'bounty emigrants', that is, people who emigrated with the assistance of money from the Colonial Government. The Harpurs, like TLM-P, were 'cabin passengers', paying their own way in superior accommodation. As well as 'Miss Matilda Harpur' and her father and step-mother 'Mr. and Mrs. Harpur', there was an elder and younger brother along with two sisters: 15 year-old Thomas Harpur,8); Miss E[lizabeth] Harpur9); Miss Rosa Harpur10) and 9-year-old Master A.H. Harpur.11)

Thomas Harpur first tried farming on the Parramatta River, then moved his family to Cecil Hills, north-west of Liverpool.12) His and Mary Jane Harpur's daughter Emily Anne was born in 1843.13) The birth notice inserted in the paper gives scant recognition to Mary Jane: it simply states that 'On the 4th instant, the Lady of Thomas Harpur, Esq., of Cecil Hills, of a daughter'.14) Like her stepsisters Matilda and Elizabeth, Emily married and lived in Queensland.15) Matilda's stepmother, described as Mary Jane Harpur nee Speer, the widow of Thomas Harpur late of Cecil Hills, died in London in 1887. Only one offspring was mentioned: Richard Harpur of Barmundoo, Gladstone.16)

Thomas Harpur was not a success in the new colony. His granddaughter Rosa Praed was an imaginative novelist rather than reliable biographer but she referred to her mother's letters when she wrote about her. Rosa considered that Thomas Harpur was unsuited to the life of a colonial bushman. Rosa quoted Matilda writing to her fiancée bemoaning that their property was plagued by drought and bushfire while “Papa, while his bush is burning and his beasts are perishing, sits in the little parlour writing poetry… He is now writing a piece on Life which is very pretty, but Mama does not like his confining himself so much to the little parlour, for besides injuring his health, poetry also makes him neglect the station. But Papa, she mournfully adds, was never cut out to be a bushman; he is much fonder of writing poetry than of riding after cattle.”17) Thomas Harpur's poetry appeared in a Sydney Weekly called Atlas under his pseudonyms 'Harmonides' and 'Cecil Hills', and in 1847 his major epic poem, A Land Redeemed, was published.18)

His neglect of his property in favour of poetry had serious consequences: by May 1844 Thomas Harpur was bankrupt. He even had to hand over his clothes to his creditors.19) In 1846, in a flowery letter defending himself against the charge of providing 'sly grog' (home-made alcohol) and noting he was acquitted of the charge, he described himself as a 'farmer'.20) He, his wife, and two younger children had a lucky escape that year: the house caught on fire and when fighting it, a large chest was dragged out of the house, then was discovered to contain gunpowder. Thomas Harpur had brought it out 'from home', and forgotten about it! It does not suggest the kind of practical man who thrived in the colonies. The account of the 1846 fire mentions only two of his younger children, suggesting that the others had all left home.21) Thomas Harpur was still living at Cecil Hills in 1847.22) He died in 1848, aged 51.23)

Given her father's love of poetry and lack of desire to tackle alternative employment, it is understandable that numerous writers have assumed that Thomas was the brother of the prominent colonial poet, Charles Harpur. Additionally, Matilda also was a talented writer, though her talent was used mainly used to educate her children to appreciate English literature and history. Charles Harpur, like Matilda, was also to die of tuberculosis.24) However, as biographer Patricia Clarke has outlined, a shared surname appears the only traceable family connection.25) None who assert that Charles and Thomas Harpur were brothers have provided any evidence of the supposed relationship. Thomas Harpur was born in Ireland in 1797, migrating to Australia in 1840. Charles Harpur was born in Australia in 1813; his parents were both convicts and married in 1814. Charles' father, who had been a school master, was transported for highway robbery in 1800.26)

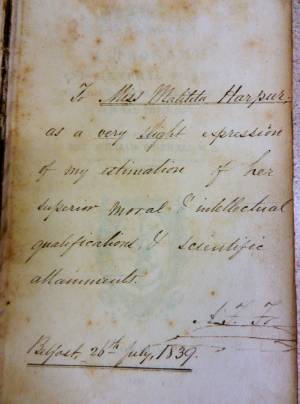

What little we know about Matilda is all positive. In 1900, her daughter Rosa recalled her mother in idealistic terms, remembering how she would sit on a log with her 'tired mother … [her] pale sweet face, the bright eyes, the fragile form, in which spirit strove sometimes vainly to overbear weakness of flesh … [talking of] aspirations after higher things…. Our mother was a wise woman and most tenderly sympathetic' and so first planned the Maroon Magazine. It was educational in purpose, Rosa realised, but it was also play 'and therein lay our joy'.27) It confirms that the Harpurs were Protestant with evangelical leanings, and that they lived in College Square, Belfast. It also provides evidence that Matilda Harpur was considered exceptionally bright.

Title page and dedication of the book presented to Matilda Harpur.

Title page and dedication of the book presented to Matilda Harpur.

The (teacher's?) initials may be 'A.F. Fr.' and it is dated Belfast 26 July 1839. The book is typical of its era in its presentation of science as evidence of God's creation. It is hardly light reading, especially for a 12-year-old! Its excellent condition may be because it was treasured - but equally probably, because it was little read.

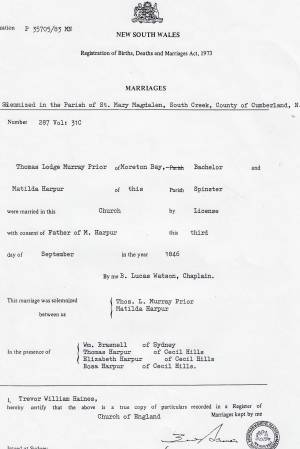

If Matilda had been a boy, what use would she have put her scientific and intellectual ability? As it was, the following year she migrated to Australia and 6 years later, on 3 September 1846, aged 18, married 26-year-old TLM-P at St. Mary Magdalene Church of England, South Creek, Cecil Hills.28)

29)

29)

It appears that Matilda and TLM-P had been writing to each other since the year after she arrived in the colony, that is, from the time she was 13 or 14 years old.30) While the letters allowed some familiarity, TLM-Ps efforts to establish himself in the north allowed little opportunity for visits. It also meant anxiety and long silences. Rosa Praed states that one of Matilda's letters took over five months to reach TLM-P, 'and then only through his chance meeting with the person who had bought in north, when Murray-Prior was delivering a mob of bullocks to the butcher in Brisbane.' There was reason for anxiety though one of Matilda's comments suggest that her fears were based on sensationalism rather than the more prosaic reality of Aboriginal people defending their land (but not being cannibals), or the ever-present danger of accidents and illness far from help. According to Rosa, Matilda wrote in her letter that, 'I am indeed thankful to know by the sight of your handwriting at last that you have not been murdered by bushrangers or eaten by Blacks.'31) Another time, again according to Rosa, TLM-P complained about her restraint (quite understandable if her father or stepmother read her letters, as was conventional at the time). Matilda asked 'Have I not given you the best proof of my affection and confidence in consenting to share your fortunes?'32) For a ardent young man angling for a declaration of passion, it was a dampening reply.

Death

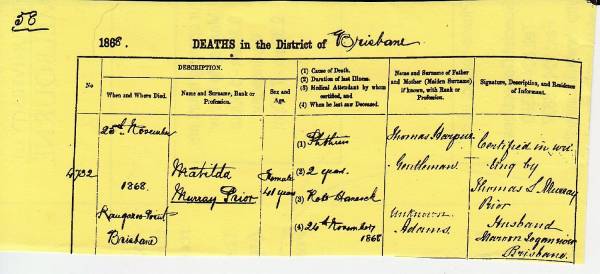

Much to the grief of her children, Matilda died of consumption (tuberculosis)33) when she was 41 years old at their home 'Montpelier' at Kangaroo Point, Brisbane on 25 November 1868 and was buried in Brisbane Cemetery. She was not alone in suffering from tuberculosis in this pre-vaccination era: in Queensland it was the 'largest single killer of working adults throughout the colonial period', though Pacific Islanders were particularly susceptible. As well, at the time Queensland had a higher death rate from the disease than England.34) Matilda's death certificate indicates that the diagnosis was made two years before she died, shortly after the birth of her last child, Egerton.35) TLM-P's diary indicates that he was concerned enough about her health in 23 September 1864 to consider taking leave of absence from his employment as Postmaster-General.36) Another possible indication of prolonged ill-health are the cheques to pay chemist bills in 1866-67 e.g. in June 1866 Mr W.J. Page Chemist was paid £3.16.6 and in June 1867 £5.7.3. As well there is a note in September 1867 regarding a cheque for £3.11.0 to Dr Hugh Bell that TLM-P thought had been paid previously. In March 1868, Dr Handcock was paid with a cheque for £10.8.6, suggesting numerous visits.37)

Grief at her loss lingered. In 1882 her widower visited Lady Bowen, the wife of the first Governor of Queensland: she 'had tears in her eyes naming Matilda. She [Matilda] was so good, so kind she had never met a more unselfish woman'. Lady Bowen shook her head at the news TLM-P had remarried 'and still more when in reply I told her I had more children'.38) TLM-P's list of cheques indicates that the regard was mutual as in October 1867 both Matilda and Rosa paid for a testimonial to Lady Bowen, respectively costing £3.3.0 and £1.39)

Family circle

Matilda's sisters Rosa and Elizabeth Harpur visited her after her marriage and they too married Queensland squatters. These relatives were especially important given the small (white) settler population - Queensland only had around 30,000 settlers in 1861, and about two-thirds were men.40)

Elizabeth Harpur married William Barker of Tamrookum station on 8 July 1847: TLM-P was one of the witnesses.41) Tamrookum was just south of the town of Beaudesert and, using today's road, is around 33km from Maroon and around 12km north of Rathdowney. Elizabeth and William Barker had six sons and two daughters.42) In the late 1860s, the well-known poet and novelist, James Brunton Stephens, was employed as their tutor at Tamrookum. TLM-P's ledger for Bugrooperia indicates that he had business dealings with William Barker and Tamrookum43). A Hawkwood ledger c.1856 lists 'Mr J. B. Stephens' buying stores including books costing £4.5.6.44) William Barker sold Tamrookum station in 1878. In 1927, the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King and Queen) stayed at Tamrookum which was described as 'about 45,000 acres' with the homestead 'a lovely old home built almost entirely of cedar' and with 'about 30 rooms' situated 'on the slope of a hill overlooking a beautiful crescent-shaped lake'.45)

Six years later, on 3 September 1853, Rosa Harpur married Charles Robert Haly (1816-92). Again TLM-P was one of the witnesses who signed the marriage register.46) Rosa and Charles Haly lived at Taabinga Station in the Burnett district until he was forced to sell it due to 'diseases in his sheep and the rapid spread of speargrass'. In 1882 he became police magistrate at Dalby where, from 1891, he was also clerk of Petty Sessions. He died the following year, reportedly survived by 11 of his 14 children.47) See also Elizabeth Caffery & George Groves, The Gathering of the Waters. A short history of the Nanango Shire,Nanango Shire Council, 2007; Rosa Harpur, Queensland marriage certificate, 1854, BM227.)) In 1881, Nora M-P considered possible people who could help her stepdaughter Lizzie look after the children at Maroon while Nora had her baby in Brisbane. She mentioned Rosie Haly as a possibility, 'in default of anyone more interesting'.48) Rosa Jane (Rosie) Haly was then 19 years old.49) In 1882 TLM-P visited Captain O. G. Haly when he saw the name on an office in the army's Intelligence office, where he was visiting one of his second wife's relatives. Captain Haly had been close to Charles Haly's brother William. The brothers had migrated together to Queensland, with Captain Haly commenting that 'all the sons of the family are in Australia'.50).

The three Harpur sisters and their families were close, and the small European population promoted everyday interactions.51) TLM-P's diaries indicate that the relationship between the families remained close after Matilda died and he remarried. TLM-P also had business dealings with his brother-in-law Charles Haly including lending him money to mortgage land.52) A note in TLM-P's 1864 diary refers to him paying interest, and that TLM-P offered to sell him some land.53) As well, Haly also occupied TLM-P's property Creallagh in 1863. TLM-P's ledger entry for 5 May 1867 has a heading Chas R. Haly Esq and the explanation that 33 acres of land at Indooroopilly occupied by Mr Pitman had been originally sold to A. V. Drury Esq. then the mortgage transferred to (his brother) Ed. Drury (the sons of TLM-P childhood teacher in Brussels, the Rev. William Drury) and afterwards to C.R. Haly. TLM-P paid £330 and three interest payments at 10 per cent. By January 1868 he had paid the capital and interest totally £360.14.9. 54)

Another witness to Charles Haly and Rosa Harpur's marriage was Charles' brother William O'Grady Haly. 55) He also illustrates the close-knit nature of Queensland society. 'Mr O'Grady Haly' had been superintendent at Maroon to an earlier owner of that property.56) When he (or a namesake died), TLM-P was a co-trustee/executor.57) Similarly, the small circles in which they moved is illustrated by the experience of Matilda's other sister Elizabeth. When her husband William Barker retired from Tamrookum, they purchased Nunnington, a house at Kangaroo Point, Brisbane. It was sold to them by Frederick Orme Darvell, then Registrar-General of Queensland, and Nora M-P's uncle. Nunnington was named what the Darvalls believed to be a family home in Yorkshire.58)

Evidence of the literary bent of Matilda and her children survive in few copies of a hand-written family magazine that they produced at Maroon and called Maroon Magazine. The children's cousins, the Barkers, and James Brunton Stephens also contributed.59) Three issues are in Rosa Praed's papers in the John Oxley Library. For more click on **Magazine**. In the early years at Maroon, the family's literary activities were likely to have been briefly enhanced by the appointment of a new manager on 3 July 186560) of William Traill. It appears, however, that he only lasted three months as he kept selling the prime steers.61) He later become a well-known journalist.

European women living in what is now Queensland had a higher number of children than their sisters in the south, a phenomenon that was strongly supported by TLM-P and other politicians, 'spurred by fears of being engulfed, both numerically and culturally by foreign invaders'.62) Matilda was exemplary in this regard: she had 12 children during her 22 years of marriage. It is likely that her fecundity contributed to her early death aged 41. Additionally, each time she gave birth there was a real possibility of dying in the process: in 1878, for example, a pregnant woman in Queensland had 'one chance in 21 of dying in childbirth'.63) In addition, Queensland's death rate was higher than that of other Australian colonies.64)

Matilda and TLMP's Children

Matilda had her children when her husband was struggling to establish himself. They were not wealthy at this stage and, at least for her first six births, she endured the rough isolation that characterised the life of women settlers in rural Queensland at the time. Repeated childbearing - in this age when abstinence was the only effective contraception - undermined her health. Matilda had 12 children during 1848-66. One way of looking at this is that she was pregnant for exactly half those 18 years, during which time she also raised eight and buried four of her children. It did not make it any easier that having four of her children die before her was statistically normal. Even in Victoria in the 1880s and 1890s, where health outcomes where better, by the time a married woman was 50 years old, typically 'about one-quarter of her children would have died'.65) It is also possible that she was pregnant at other times as we don't know if she had any miscarriages or stillbirths (stillbirths were not registered in the 19th century).

For Matilda, the toil of repeated pregnancies was eventually combined with tuberculosis. The result was tragic for all concerned. The last stages of tuberculosis leaves little doubt that the sufferer is dying, so Matilda would have known she was leaving behind motherless children. When she eventually succumbed, her 8 surviving children ranged in age from 20 to 2 years old. They were:

1. Thomas de Montmorenci 27 January 1848-11 December 1902.66)

2. William Augustus, 8 August 1849 - 17 January 1850

3. Rosa Caroline, 27 March 185167) - 2 April 1935

4. Morres, 1568) May 1853 (no online record of his birth being registered has been found) - 2969) October 189770)

5. Elizabeth (Lizzie) Catherine, 29 October 185471) - 19 December 1940

6. Hervey Morres, 9 September 185672) - 1 January 188773)

7. Redmond, 26 October 185874) - 21 January 191175)

8. Weeta Sophia, b. 24 June 186076) - 27 July 1860 77)

9. Hugh, 25 or 26 July 186178) - 28 December 189579)

10. Lodge, August 186380) - September 1863.81)

11. Matilda, 2682) January 1865 - 11 May 1865.83)

12. Egerton, 5 October 186684) - 1 September 1936.

For more details see sidebar entries for Thomas de M. M-P and his siblings. For the children's, mainly the boys', education see Boys' and girls' education.