Table of Contents

Character, Possessions, Photos

TLM-P's actions and possessions as well as his writings reveal much about his character, and this section gives additional hints about what he was like.

Character

The view of Australia's Representative Men was that TLM-P had a 'most courteous manner and kindness of feeling'. Further, 'all classes can approach him and be received without ostentation'. His private character matched his public image, with his 'family and acquaintances' holding him 'in great esteem'. He retained strong ties to his country of birth, returning there on visits in 1881, 1885 and 1888.1)

TLM-P's son Robert, who was 11 when his father died, agreed. He described TLM-P as 'justly renowned for his courtly bearing and usage of words. He was veritably an aristocratic statesmen of old and could smile through the harshest of Parliamentary insults' The only thing that cause him to lose his temper was any insult to Queen Victoria or towards 'Monarchy as a phenomenon', on the apparent grounds that the Queen was 'his distant cousin'.2) This view of TLM-P has been accepted unquestioningly by other writers, perhaps most influentially in his entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Certainly if he adopted an overly courtly bearing, it fits in with Rachel Henning's perception of him in 1863 as 'I suppose it does not require any great talent to be a Postmaster General. I hope not, for such a goose I have seldom seen. He talked incessantly and all his conversation consisted of pointless stories of which he himself was the hero.'3) Yet TLM-P's diary for 6 October 1863 suggests a more pertinent reason: he described the Henning's house as 'a comfortable humpy' and dismissed Rachel and her sister with the slighting comment that 'Mr Henning … has unmarried sisters living with him, somewhat passed their first youth'. It should be noted too, that TLM-P may not have been at his best: he stayed with the Hennings while on a tour of inspection that would leave most people exhausted: during 54 days inspecting postal services, he rode 1,017 miles (1,636 km) as well as travelling by sea. Additionally, if TLM-P was such an ardent monarchist it did not stop him marrying Nora Barton who blithely wrote to his elder daughter that of course she thought Australia should become a republic, though she did not expect it until the next generation!4)

TLM-P's conflict with Elise Barney of the Brisbane Post office has made him somewhat of a feminist anti-hero, but neither his two choices of wife, his support for his daughter Rosa's career, nor his will, supports the view of him as a general oppressor of women. In his will, he made it clear that his bequests to his wife and daughters were all 'for her separate and inalienable use … free from marital control or engagements'. While trustees still controlled his second wife's money, he did appoint her relatives to act in her interest and furthermore gave her the right of choice between continuing with her marriage settlement, or accepting £10,000 (roughly equivalent to $1,427,346 in 2017 values) instead.5)

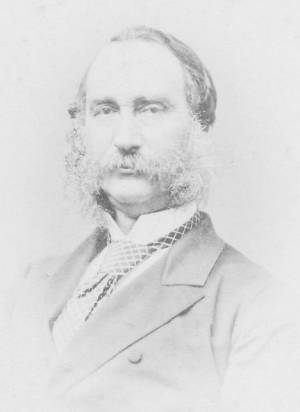

The first two photos from TLM-P's album6) were taken in Melbourne; the last in Sydney. The images are designed to reveal a prosperous man who has succeeded in his adopted land. For more photos of him, click on TLM-P photographs.

The first two photos from TLM-P's album6) were taken in Melbourne; the last in Sydney. The images are designed to reveal a prosperous man who has succeeded in his adopted land. For more photos of him, click on TLM-P photographs.

Furniture and other possessions

The beautiful furniture that TLM-P owned reveals that he shared his father's tastes for fine art and household items. It also supports the interpretation that TLM-P was motivated by his determination to restore his family's gentry status. The next photo is of his intricately carved Indian cabinet,7) the twin of which is in Brisbane's Tattersalls Club. As usual with such furniture, it neatly comes into sections:

This Chest with mirror belonged to Thomas B. and Lizzie M-P.8)

The family has numerous examples of Australian red cedar furniture which has been passed on through the generations from TLM-P and his family. This elegant table with chairs is one example.9)

A very different watch, made in France[check?], and thought to have belonged to TLM-P.10)

A very different watch, made in France[check?], and thought to have belonged to TLM-P.10)

TLM-P, once he had his family's entitlement to arms cleared, had his silver engraved. This plate is an example.11)

TLM-P, once he had his family's entitlement to arms cleared, had his silver engraved. This plate is an example.11)

Colonial Masculinity

A much more problematic aspect of TLM-P's career is the connection between nineteenth century masculinity, the brutal takeover of aboriginal lands, and the colonial imperative to (as it was later put) 'populate or perish'. Nineteenth century Queensland was relatively isolated and sparsely populated by whites, so settlers like TLM-P idealised the land as 'vast uninhabited stretches of country waiting to be filled by resolute, hardworking Britons … Progress - conceived in the masculinist framework of aggressive expansion, ruthless destruction of the Aboriginal people, economic development and environmental exploitation - needed not only capital, brawn and sheer determination to succeed, but healthy young citizens'.12)

Historian Angela Woollacott has argued, using TLM-P as a case study, that the concept of manhood in the colonies was intertwined with acceptance of frontier violence. She unquestioningly accepts Rosa Praed's version of events despite Rosa never quite making the transition from being a novelist to that of an accurate memoirist. She also attributes TLM-P's memoir of the Hornett Bank massacre to Rosa. Nevertheless, her argument, supported by other historians, is worth considering: that 'frontier violence was accepted within evolving definitions of manhood and hence political responsibility … when we link frontier violence to gendered authority, mid-nineteenth century ideas of manhood might look a little less peaceable and restrained'.13)

I suspect that TLM-P was too complicated to be a satisfactory stock figure in any historical argument, though it would be possible to mount a case that his identification with royalty, insistence on a 'courtly' bearing and even his art collection that he bequeathed to the public, was at least partly motivated by a desire to assert himself as a civilised man, and to distance himself from his part in the grim reality of wrenching land from its traditional owners.